After our initial report on AmTrust Capital (AFSI), “Amtrust Financial Servies: A House of Cards?“, Bronte Capital (“Bronte”) criticized the report as a “hit-piece” with “howling error after howling error”. We stand by our report and appreciate the opportunity to provide additional clarity.

Readers should know that we attempted to reach out to AFSI prior to our report both by phone and email to ask questions and received no response. In contrast, Bronte, who “once respected our work”, did not provide us the same courtesy before criticizing our report and suggesting AFSI is “the perfect candidate for a ‘short squeeze'”. Constructive criticism is welcome, but warnings of a “short squeeze” because short sellers “do not understand what they are short” are misguided.

We detail below why we disagree with Bronte’s contention that our report contained errors and provide additional details so that readers can better understand what is most certainly complex accounting. We believe Bronte’s post criticizing our report misses several key points in our report and that Mr. Hempton’s subsequent comment about ceded premiums (earned) and ceded losses (incurred) actually implies that he agrees with our approach. We believe Bronte may revise its view after re-reading our initial report along with the clarification we provide below.

Reinsurance Accounting

Bronte criticized our report for making “accusations of reinsurance accounting fraud by someone who does not understand what is meant by ‘ceded losses'”. The crux of Bronte’s criticism appears to be the following:

“Geoinvesting has simply added up the “losses ceded” to the (internal) reinsurers and wondered why the “losses” did not wind up in the P&L.”

Response #1 re: ACHL

Bronte seems to be saying that we are confusing the “Ceded Incurred Loss & LAE” (the provision / expense in the income statement) with net losses (revenues less expenses such as loss expense incurred), implying that we ignored premiums ceded. This would seem to be confirmed by the comment Mr. Hempton made within the comment stream (December 15, 2013 at 5:13 PM) of Bronte’s blog:

“Its (sic) relatively simple: when you cede the loss you cede the associated premium”.

Bronte appears not to have read our report very carefully because this was effectively our criticism of AFSI ”’ losses were ceded (from AII Bermuda to ACHL Luxembourg) without ceding any associated premiums. In such a scenario ceded losses should approximate the net loss (assuming zero ceding commissions).

We refer you to the section of our report titled “Proof That ACHL Received Zero Premiums”, which we have excerpted below for the readers’ convenience.

Proof That ACHL Received Zero Premiums

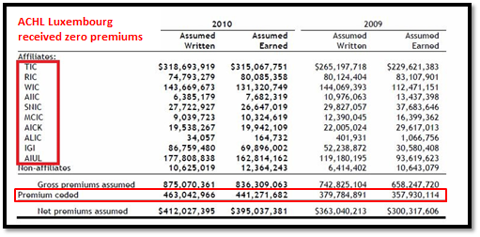

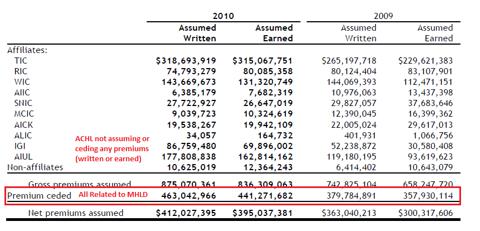

AII Bermuda’s 2010 financial statements break out premiums assumed and premiums ceded for 2009/2010, which we show below.

Source: AII Bermuda’s 2010 Audit

Notice that ACHL is not presented in this table provided by AII Bermuda. Affiliates TIC through ALIC are AFSI’s regulated US subsidiaries. IGI is the holding company for AEL, AFSI’s regulated UK subsidiary. AIUL is AFSI’s regulated Irish subsidiary. Finally, “Premiums Ceded” relate to Maiden Holdings (MHLD) and not another entity, as evidenced by AII Bermuda’s Reinsurance Footnote which we show below:

Source: AII Bermuda 2010 Audit

Response #2 re: ACHL

Bronte’s “explanation”, which was inset like a quote from Wikipedia, despite our inability to find that passage on the Wikipedia link provided by Bronte, said:

“When an insurance policy is written the insurance company “writer” will recognize as an asset the premium received. They will also recognize a “loss reserve” an amount being the amount they will expect to pay out on the policy over time.

This “loss reserve” is not a loss. Its (sic) simply a reserve for future payments. Whether the policy makes a profit or loss will be determined as the decades roll on. [If it is a workers (sic) compensation policy for instance an insurer may be paying an injured worker’s medical bills thirty years hence…]

In a typical (and in this case proportional) reinsurance arrangement, a reinsurer takes a stated percentage share of each policy that an insurer produces “writes”. This means that the reinsurer will receive that stated percentage of the premiums and will pay the same percentage of claims. In an accounting sense this is called “ceding the loss” and “ceding the premium” to the reinsurer. The reinsurer also recognizes no loss in the P&L. The gain or loss of the policy is recognized over decades.

In addition, the reinsurer will allow a “ceding commission” to the insurer to cover the costs incurred by the insurer (marketing, underwriting, claims etc.).”

We found this explanation is rather convoluted and mixes balance sheet items with income statement items. Please see the appendix for a detailed walk through of the accounting entries one should expect an insurance company to make and how these arrangements affect the income statement.

Here’s what we think Bronte meant to say:

When an insurance policy is written, the insurance company “writer” will recognize an asset on the balance sheet (cash or premium receivable). They will also recognize a liability for “unearned premiums” on the balance sheet as well (think deferred revenue). Over the term of the policy, the unearned premiums will be earned through the income statement as revenue.

As the premium is earned, the company will recognize the incurred loss and loss adjustment expense (provision) which goes to build the loss and loss adjustment reserve (a liability for estimated future claim payments). As the decades roll-on, the company will recognize increases (decreases) in the estimate of claim payments for previously earned policies as adverse (positive) development which is added to (subtracted from) the loss provision for newly issued policies.

It is unclear what the exact nature of the reinsurance agreement between ACHL and AII is, but it’s clearly not proportional (because AII has more premiums than loss provisions while ACHL is the opposite as evidenced in AII’s financial statements).

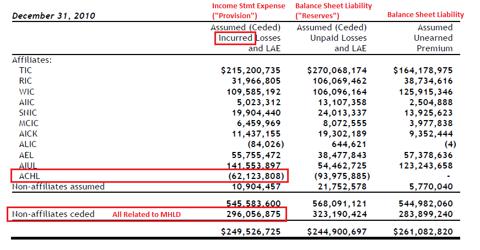

The financial statements showed that AII did not cede any premiums earned (or written) to ACHL in 2010, so ACHL will not recognize any “assumed premiums earned” on its income statement. However, we also showed that AII did cede ACHL’s $62.1 million of losses, so ACHL should recognize $62.1 million of “assumed loss and loss adjustment incurred“. As such, we would expect ACHL to report a net loss of $62.1 million for 2010. (net loss = $ zero assumed premium earned minus ceded losses incurred of $62.1 million).

Since ACHL is a wholly-owned subsidiary of AII, we believe these transactions should be unwound upon consolidation when preparing AII’s financial statements. However, AII uses the equity method to prepare the AII 2010 financial statements, so that is not the case. Below is an excerpt from BDO’s Independent Auditor’s Report from AFSI’s 2010 10-K (emphasis added):

“As discussed in Note 2 to the financial statements, the Company (AII) accounts for its investment in AmTrust International Underwriters (“AIUL”), AmTrust Europe, Ltd. (“AEL”), AmTrust Captive Holdings Limited (“ACHL”) and AmTrust Insurance International Management (“AIIM”), wholly-owned subsidiaries, on the equity method of accounting. Accounting principles generally accepted in the United States of America require that all majority-owned subsidiaries be accounted for using the full consolidation method.”

Life Settlements

Bronte Capital appeared to criticize our report ‘s content regarding life settlements relating to (1) life expectancies (LEs), (2) the discount rate, and (3) Phoenix-issued policies. Below, we will counter those criticisms in detail.

First, we thought it would be helpful to discuss life settlements generally. Bronte said “Surely some of them have died. So far they have not had any trouble collecting – the idea that these policies should be held by AmTrust at pennies on the dollar is ludicrous.”

The question is not whether AFSI has collected on mortality events to-date (it has). When the underlying insured dies early, the life settlement investor gets a windfall. That doesn’t mean that the remaining policies are worth much (or anything). The real question to ask in evaluating any company’s life settlements is:

What is the probability-adjusted PV of the death benefit, net of the probability-adjusted PV of the premiums the policyholder will have to pay to receive the death benefit?

As long as the insurance company issuing the policy hopes to make a profit, the answer to that question should always be less than zero because the insurance company embeds a margin (think house advantage at a casino). In other words, buying an insurance policy is a negative NPV proposition. If someone’s health deteriorates (gambler gets a hot hand), that policy becomes more valuable and the policyholder could sell it for something in excess of the cash surrender value that the issuer would pay.

Now consider a policy issued by an insurance company on a 74 year old person in 2007 (approximately what AFSI owns (see footnote 1). First, the insurance company is still going to embed a margin to issue the policy. Second, the insurance company is going to think long and hard about the risk of issuing a policy to a 74 year old because that person’s life expectancy is obviously short. As important, the risk of adverse selection is incredibly acute. This is in contrast to the more familiar example of a young family buying a policy on the breadwinner because the risk of losing that person’s income would put them at unacceptable risk. In other words, the young family is much less likely to be attempting to “pick off” the insurance company.

In addition, an insurance company presented with a wealthy (see footnote 2) 74 year old is likely going to say:

“What risk are they looking to protect? They’re already retired, paid for their kids’ college, and can live comfortably should the insured pass-away. Perhaps, this is a premium-financed policy. If that’s the case, I need to lower my lapse assumption because investors are much less likely to voluntarily lapse the policy.”

Lastly, it’s worth noting that AFSI’s premium-finance loans almost universally (disclosures are vague) defaulted. Had there been any adverse developments in the insured’s health, the seemingly wealthy (see footnote 3 insured would use their considerable resources to pay off the loan and keep the suddenly very valuable policy instead of allowing AFSI to benefit from the windfall.

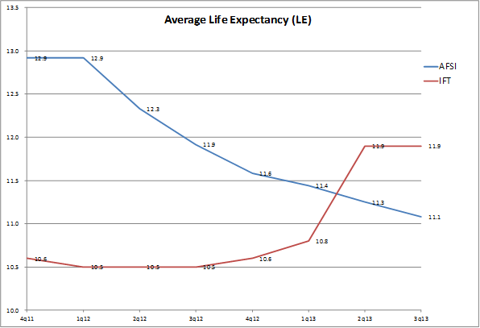

Bronte Contention #1: AFSI’s LE’s seem reasonable

Bronte contends that AFSI’s LE assumptions are not “inherently implausibly low” because the company assumes the average insured will live to an average age of 91. Bronte goes on to say that the company lengthened the average life expectancy which lowers the expected value of the policies, and cited the increase in estimated average age at death of 91.0 vs. 90.4.

This statement, along with subsequent comments about life settlements, demonstrates Bronte’s lack of familiarity with the subject.

According to the 2008 VBT table (see footnote 4), if a 77 year old male (female assumptions in parentheses) with standard life expectancy has an LE of 8.25 (see footnote 5) (10.39) years. If he (she) lives for two years, his (her) LE is not 6.25 (8.39) years. It is approximately 7.16 (9.06) years.

Additionally, Bronte appears to have ignored our report’s reference to 21st Service’s January 2013 increase in LEs. The 19% increase in average Les (see footnote 6) as the most commonly used LE provider caused waves throughout the life settlement industry. The 19% average increase likely understates the impact to AFSI because adjustments for anti-selection related to premium-financed policies, which comprise the vast majority of AFSI’s policies, were even greater (see footnote 7).

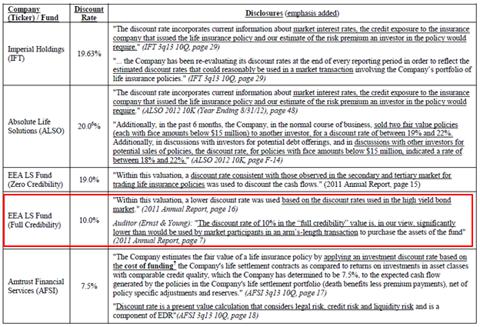

Bronte Contention #2: 7% Doesn’t Seem Unreasonable

Without substantiation, Bronte says 7% (it’s actually 7.5%) “doesn’t seem unreasonable”. However, ASC 820 (Fair Value) requires the use of market-based measurement (see footnote 8) (see below) which, based on peer disclosures, appears to be closer to 20%.

“820-10-05-1B Fair value is a market-based measurement, not an entity-specific measurement. For some assets and liabilities, observable market transactions or market information might be available. For other assets and liabilities, observable market transactions and market information might not be available. However, the objective of a fair value measurement in both cases is the same-to estimate the price at which an orderly transaction to sell the asset or to transfer the liability would take place between market participants at the measurement date under current market conditions (that is, an exit price at the measurement date from the perspective of a market participant that holds the asset or owes the liability).”

As discussed in our report, Ernst & Young disagreed with EEA Life Settlement Fund’s valuation of LSC because they used a 10% discount rate (after adjustments to improve the accuracy of other inputs):

“The discount rate of 10% in the “full credibility” value is, in our view, significantly lower than would be used by market participants in an arm’s-length transaction”.

The report also noted IFT and ALSO’s market-based discount rates were approximately 20% and included the table below to demonstrate:

Bronte Contention #3: “Phoenix Looks Like It Will Survive”

Bronte also countered our concerns about AFSI’s Phoenix-issued policies by stating that Phoenix “looks like it will survive”. As proof, Bronte said the “regulator is even allowing the insurance company to pay almost (sic) 30 million in dividends to the parent company” and cited a press release noting PLIC paid a dividend to the holding company.

Here is where we differ from Bronte:

1. Bronte Is Looking At The Wrong Phoenix Subsidiary (see footnote 9)

The dividends allowed were from Phoenix’s principal operating subsidiary, Phoenix Life Insurance Company (PLIC). However, AFSI’s policies were issued by another subsidiary – PHL Variable, which is why PHL was named in the Tiger Capital lawsuit. In the interest of brevity, we referred to Phoenix (PNX) in our initial report because even PLIC-issued policies also trade at substantial discounts. However, if Bronte still disagrees with us, Fortress would probably be ecstatic to sell them PLIC (or PHL Variable) policies at a 10% discount rate (according to Bronte, a bargain).

2. Bronte Is Uncharacteristically Cavalier In Its View Of Phoenix

It’s almost hard to imagine the Bronte we thought we knew points to (1) the wrong subsidiary and (2) the action of regulators regarding a sister company as confirmation that PHL Variable issued policies are money-good. Regulators do their best, but they are not all-knowing.

We won’t claim perfect foresight with regard to Phoenix and do not have a view on the adequacy of their reserves (life insurers are even harder than P&C). However, we know that PHL Variable has $62.8 billion and $14.0 billion of gross and net life insurance, respectively, in-force (whole life and term) as of December 31, 2012. In addition, PHL has $1.6 billion of annuities subject to guarantees — an area many life insurers have been desperate to sell because of the severe risks. Against these incredibly large risks, PHL has merely $272 million of capital. That’s not an entity to which we would pay premiums for the next 12 years in the hope that we realize a 7.5% IRR…

For the edification of readers, the typical state guarantee fund is capped at $300,000 of policyholder benefits. That means that AFSI might pay premiums for twelve years only to receive ~5% ($300k / $6.7m average face value) of what they expected for a death benefit after having paid premiums far greater (admittedly the worst case scenario).

3. Bronte Ignored Non-Bankruptcy Risks

The Fortress complaint cited in the report noted “anti-competitive and exclusionary conduct” has “destroyed the value of Phoenix policies and robbed policyholders of the once-precious ability to sell their policies in a competitive market.” This quote demonstrates that Phoenix (PLIC or PHL Variable) policies are disdained by market participants not just for the risk of insolvency but also for Phoenix’s predilection for aggressive tactics towards life settlement investors.

This is evidenced by the fact that Tiger Capital sued PHL Variable for significantly increasing the cost of insurance (COI). Our original report linked to a copy of the complaint. An increase in the COI means AFSI will pay higher premiums without the potential for any increase in the death benefit. In other words, Phoenix lowered the value of AFSI’s policies.

Additionally, Phoenix has been willing to fight paying death benefits in a myriad of circumstances and contest the insurable interest of various parties well beyond the standard two year contestability period — often with success.

As such, owners of Phoenix-issued policies are likely to pay higher premiums than initially expected, face higher litigation costs and uncertainty of outcomes even when the things go their way, and face the risk of getting paid less than expected due to insolvency risk at PHL Variable.

Concluding Comments

We appreciate a healthy debate and open discourse on investment ideas. As such, we will let the analysis presented herein speak for itself and merely say we respectfully disagree with Bronte’s view.

With regard to ACHL, we stand by and reassert that AFSI (via AII) appears to be ceding losses without ceding any associated premiums to a wholly-owned subsidiary (ACHL) and that those transactions do not appear to be properly unwound upon consolidation.

On the subject of life settlements, we continue to question the company’s valuation. In particular:

- AFSI’s discount rate of 7.5% appears too low based on peers’ comments about market transactions,

- AFSI’s LEs are oddly falling while peers’ LEs are rising — in large part because the top provider recently increased LEs by 19% on average, and

- AFSI’s significant exposure to Phoenix (PHL Variable) policies would seem to deserve a marked discount as a result of the greater risk associated and market participant comments about arm’s-length transactions in Phoenix policies (or, more accurately, the lack of buyers).

Footnotes:

- Per court filings, the policies were all issued in 2006 and 2007 – the height of premium-financed STOLI policies.

- Insurable interest laws require the buyer of an insurance policy have an interest in the insured at least as great as the death benefit.

- We say “seemingly wealthy” because premium-financed policies are fraught with fraud like over-stating the insured’s wealth in order to get larger face value policies.

- Preferred Valuation Basic Table Team

- Linear interpolation used for partial years

- Ie: 75 year old expected to live 11 years is now expected to live ~13 years.

- Discussion starts at 6:15 of 21st Services Presentation.

- Amendments to Achieve Common Fair Value Measurement and Disclosure Requirements in U.S. GAAP and IFRSs, Financial Accounting Standards Board of the Financial Accounting Foundation, May 2011, Page 191

- In the interest of brevity, we simplified the original report by referring to Phoenix policies generally because LSC issued by either entity face significant haircuts in the market for the reasons discussed in this note.

____________________________________________________

Appendix: Reinsurance Accounting

Part 1: An empirical example of reinsurance accounting

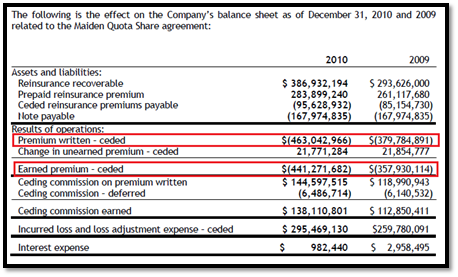

We can look at AII’s other reinsurer, MHLD to see how it should work.

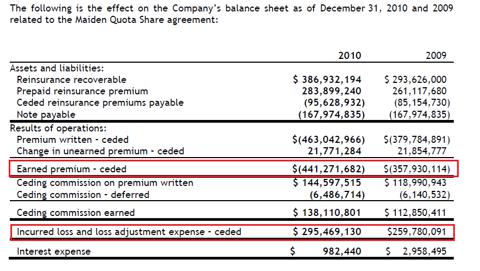

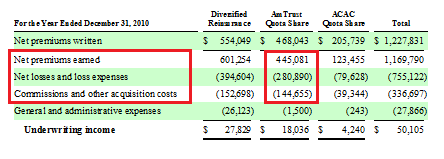

First, we can look at MHLD’s 2010 10K to see what the reinsurer recognized as earned premiums and incurred losses related to the AFSI Quota Share.

Then, we can look at AII’s disclosure for the MHLD Quota Share in AII’s 2010 Financial Statements. We see that AII ceded $441.3 million of earned premium and $295.5 million of incurred loss and loss adjustment expense which approximates MHLD’s disclosed net premiums earned and incurred loss and loss adjustment expense.

Note that $441.3 million of premium earned matches the other reinsurance footnote — the one that we use to show that ACHL receives zero premiums.

Also note that the “Ceded Incurred Loss and LAE” of $296.1 million ceded to non-affiliates very closely approximates the MHLD reinsurance footnote (minor variance which is par for the course on AFSI filings).

Part 2: Simplified example to demonstrate the accounting

Scenario #1: No Reinsurance

Assume:

- One year policy period (incurred basis)

- $100 premiums

- 60% Loss Ratio

Journal Entries:

| Event | Debit | Credit | ||

| Policy Issued (12/31) | Cash or Premium Receivable (Asset) | $100 | $100; Unearned Premium (Liability) | $100 |

| 1/1-3/31 | Unearned Premium (Liability) | $25 | Earned Premium (Revenue to Equity) | $25 |

| Provision for Unpaid L/LAE (Expense to Equity) | $15 | $15; Reserve for Unpaid Loss & LAE (Liability) | $15 |

12/31 Balance Sheet:

| Assets | Amount | Liabilities & Equity | Amount |

| Cash | $100 | Unearned Premium | $100 |

| Equity | $0 |

First Quarter Income Statement:

| Income Statement: | Amount |

| Premium Earned | $25 |

| Provision for L/LAE | $15 |

| Net Income (ignoring taxes) | $10 |

3/31 Balance Sheet:

| Assets | Amount | Liabilities & Equity | Amount |

| Cash | $100 | Unearned Premium | $75 |

| Reserve for Unpaid Loss & LAE | $15 | ||

| Equity | $10 |

Scenario #2: Proportional Reinsurance

Assume:

- One year policy period (incurred basis)

- $100 Premiums

- 60% Loss Ratio

- 40% Quota Share

Journal Entries:

| Event | Debit | Credit | ||

| Policy Issued (12/31) | Cash or Premium Receivable (Asset) | $60 | Gross Unearned Premium (Liability) | $100 |

| Prepaid Reinsurance Premium (Asset) | $40 | |||

| 1/1-3/31 | Unearned Premium (Liability) | $25 | Gross Earned Premium (Revenue to Equity) | $25 |

| Earned Premium Ceded (Revenue to Equity) | $10 | Prepaid Reinsurance Premium (Asset) | ||

| Gross Provision for Unpaid L/LAE (Expense to Equity) | $15 | Gross Reserve for Unpaid Loss & LAE (Liability) | $15 | |

| Reinsurance Recoverable (Asset) | $6 | |||

12/31 Balance Sheet:

| Assets | Amount | Liabilities & Equity | Amount |

| Cash | $60 | Unearned Premium | $100 |

| Prepaid Reinsurance Premiums | $40 | ||

| Equity | $0 |

First Quarter Income Statement:

| Income Statement: | Amount |

| Gross Earned Premium | $25 |

| Earned Premium Ceded | -$10 |

| Net Premium Earned | $15 |

| Gross Provision for L/LAE Incurred | $15 |

| Ceded Provision for L/LAE Incurred | -$6 |

| Net Provision for L/LAE Incurred | $9 |

| Net Income (ignoring all other) | $6 |

3/31 Balance Sheet:

| Assets | Amount | Liabilities & Equity | Amount |

| Cash | $100 | Gross Unearned Premium | $75 |

| Prepaid Reinsurance Premiums | $30 | Gross Reserve for Unpaid Loss & LAE | $15 |

| Reinsurance Recoverable | $6 | Equity | $10 |

Disclosure: Short AFSI