Behavioral finance is central to value investing. This is a quote that Jim Kelly, director of the Gabelli Center for Global Security Analysis at Fordham University, stated leading up to a presentation given by Professor Andrew W. Lo on January 24, 2018 at the Museum of American Finance.

The Gabelli Center for Global Security Analysis at Fordham University was established in 2013 to support and promote investment analysis in the tradition of Graham, Dodd, Murray and Greenwald. The center offers a variety of programs and events designed to promote collaboration among its constituencies and to foster dialogue between the academic community and practitioners.

I recently came across this a video highlighting Professor’s Lo’s presentation titled: “Adaptive Markets: Financial Evolution at the Speed of Thought.” You can view the video and transcription transcribed here. Please note that the video did not capture the slides that went along with the presentation, but I obtained them from Mr. Lo, which you can view here.

[layerslider id=”39″]

Behavioral Finance – Emotions Can Affect Your Investment Decisions

If you have ever let emotion impact or threaten your investment decisions, or if you have an opinion on the Efficient Market Hypothesis, I think you will find this video presentation enlightening.

Andrew W. Lo:

…is the Charles E. and Susan T. Harris Professor at the MIT Sloan School of Management and director of the MIT Laboratory for Financial Engineering. He has published numerous articles in finance and economics journals, and has authored several books including

- Adaptive Markets: Financial Evolution at the Speed of Thought

- The Econometrics of Financial Markets

- A Non-Random Walk Down Wall Street

- Hedge Funds: An Analytic Perspective and the Evolution of Technical Analysis.

His awards include the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation Fellowship, the Paul A. Samuelson Award, the American Association for Individual Investors Award, the Graham and Dodd Award and numerous other awards and honors

Presentation Highlights

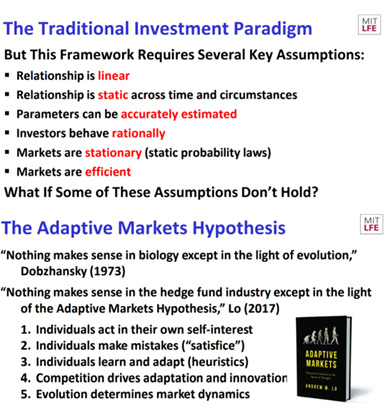

Andrew explains how he starts with an acceptance of the old school Efficient Market Hypotheses (EMH) and he then takes you through his journey of why he concludes it is not invalidated, when it appears the EMH does not hold. Specifically, he argues that the EMH is not necessarily an incorrect way to view the financial markets, but rather that during dynamic or unstable environments, the assumptions that make up the EMH are unrealistic. He expresses an opinion that the old financial models are based on static environments and need to “adapt”, as the environment changes. From there, they must take into account how investors react (behavior) to these changes. This is his basis for his “Adaptive Market Hypothesis.” Some key conclusions include: (slides 8 and 9)

He ends with a discussion how Artificial Intelligence (AI) plays a big role in our decision-making process and how AI can lead a charge to create financial products that take into account an individual’s behavioral footprint. He even touches on how record low market volatility will not last forever, and this is very interesting, given that the stock market is beginning to experience more volatility.

Professor Lo’s delivery is articulate, and the analogies he makes to non-financial situations as it relates to behavior may surprise you. For example, he references a study by economist Sam Peltzman, that shows over the long-run, U.S. regulation requiring that new cars should be made safer (reinforced bumpers, airbags and so on) essentially had zero impact on “saving” lives:

“So what he concluded is that every time one of these safety regulations was imposed, initially it reduced the number of deaths and then people adapted because there were driving safer cars they simply drove faster and more recklessly and so his conclusion was, if you want people to drive more safely, what you should do is to take way all of these safety devices and install sharp spikes on the dashboards pointing at the driver.”

Here are a few notable passages from Professor Lo’s January 24, 2018 presentation:

Impetus for the book

And the state of affairs, I suspect most of you know, is the fact that most of us who grew up in this kind of a “Neoclassical financial economics” type of a paradigm, were taught the Efficient Market Hypothesis. The idea that prices fully and everywhere and always reflect all available information. And at the opposite end of that spectrum is the fact that people are people and we engage in all sorts of human biases foibles and irrationalities.

There is a pretty wide gulf between these two schools of thought and as a graduate student, I was introduced to both of them and it was really difficult to choose, you know it’s kind of like a child listening to his or her parents arguing, you know, you just want to stop and get along and you know that they love each other but they just you know can’t come to terms. So, I decided over the course of probably now going on 25 years to try to reconcile these two warring parties and that is really the nature of this book.

What I wanted to do was to describe the different paths that I have ended up taking to try to reconcile these two schools of thoughts and really that path started off as a graduate student when I started reading a lot of the psychology literature.

Like many of you I began with the idea that markets are efficient, people behave in a rational manner and from that literature, I was brought to the psychology literature that showed all sorts of experiments, behavioral economics, behavioral finance that demonstrated that people did not react in the ways that we would predict using expectation of mere utility functions and so on.

Volatility Will Revert to The Mean

Of course, what goes up eventually does come down and so as we start adapting to this kind of a new low level of volatility there is a rude awakening that we are facing. Something to keep in mind. That is one important implication of adaptive markets. Markets are not the same over time and the population of investors they are not the same over time. They have changed and they adapt and sometimes that adaptation is positive and beneficial, but other times that kind of adaptation can be quite dangerous and detrimental.

Adaptive Market Hypothesis

The adaptive market hypothesis begins with the acknowledgement that the traditional paradigm of investment analysis, what we know and love and use in our day-to-day practices is not wrong, but it’s incomplete. It doesn’t capture the fact that in a very dynamic environment, we are not going to see the same king of relationships as in the static environment. So, when the things are stable, then stable investment policies make sense. But when things are highly dynamic, well then actually things don’t stay the same and people adapt to those kinds of changes and the fact is that right now we are living a very dynamic economy with lots of things changing even day-to-day and so the reason that many of these theories look like they are not working is not because they are wrong, but because they are not being applied to the right context and we need a meta theory to allow us to integrate all of these ideas. That is the idea behind the adaptive markets hypothesis.

Changing Environments

This is a graph of the cumulative performance over $1 investment in the S&P 500 from 1926 to the present. Now the reason you don’t recognize this, it is because I have plotted it on a semi logarithmic scale and the reason I did that was because on a log scale, it turns out that equal vertical distances correspond to equal rates of return and so if you have got an investment that has roughly the same rate of return over the time, it looks like a straight line on this graph and when you look at this graph, you see that the United States Stock market has been one of the most consistent investment in the history of capital markets . For a period of about five or six decades, the US stock market looks like a straight line. It turns out that during this period, the assumptions that I showed you on the previous page were an excellent approximation to this much more complicated reality. Does not much matter where you invest during that period of the 1930’s to the early 2000’s, you would have earned approximately a risk premium of about 8% with an approximate standard deviation of about 15-20 %. Pretty reliable risk reward trade-off during that period of time.

But take a look at the last 15 years. Do you believe that the last 15 years is just like the previous 50? If you do then you don’t need any other theories, the traditional efficient markets hypothesis, Cap M and all of the various different implications are just fine. But I would argue that the last 15 or 20 years, it does look a little bit different and there are reasons that I will give you in a few minutes why I think there are very different. And in case you want to see a better example of this kind of a difference, let me show you Japan. So, this is the Japanese stock market form 1940’s to the present. They also had their period of about 20 or 30 years of very, very stable performance in the Japanese stock market. But starting in the 1980’s, they ran into a problem, as I am sure all of you know, and the lost decade became the lost two decades and now we are running on the lost three decades in Japan. So once again, you look at this and you ask yourself well do you think that the last 30 years was just a minor blip in an otherwise upward trending curve or did something change? I would argue that something has changed and so the adaptive market Hypothesis takes change seriously and asks the question, what are you going to do about that change. How are you going to respond? How will you adapt to that change?

The basic idea behind the adaptive market hypothesis really follows that of evolutionary biology – and the great evolutionary biologist Theodosius Dobzhansky once said that nothing in biology makes sense, except in the light of evolution and so I am going to steal his phrase and repurpose it for our current context, which is that nothing in the financial industry makes sense expect in the light of adaptive markets and I am going to try and convince you of that by giving you some examples.

Alternative Take on EMH as it relates to GARP Microcaps

Many of us do not accept the tenets of the efficient market hypothesis when it comes to investing in microcap and nanocap stocks (market capitalizations less than $300 million). At times, I will even attempt to exploit inefficiencies in stocks with market caps up to $1 billion. Peter Lynch handily beat the market by investing in stocks with market capitalizations up to $5.0 billion. You can see Lynch’s stock picking guidelines here.

As a microcap and nanocap investor, I found Professor Lo’s topic to be extremely interesting. We can poke holes in the traditional definition of the EMH because microcap returns have been proven to beat out bigcaps and the market over time, by a wide margin. Here is the classic definition of the EMH:

“The efficient market hypothesis (EMH) is an investment theory that states it is impossible to “beat the market” because stock market efficiency causes existing share prices to always incorporate and reflect all relevant information.”

This definition is fairly strict. I think most of us would insert “quickly reflect all relevant information.”

Mr. Lo’s presentation can inspire us to inspect the EMH a little more thoroughly than we may have in the past. It’s standard practice to presume that the higher than “market” returns we are able to get by investing in microcaps are due to a variety of factors, such as risk aversion, low liquidity aversion, lack of institutional interest and a less fluid flow of information when compared to bigcaps. However, after viewing Lo’s presentation, one could start to at least consider this subject from different angles.

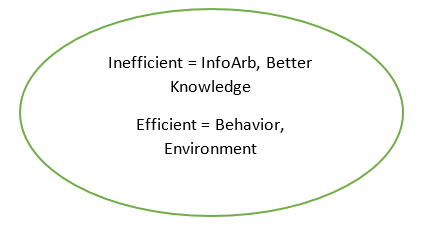

A question that popped into my head included: How should we be defining ‘efficient’?

Is it really inefficient that microcaps should offer investors higher rates of return? With Lo in mind, the answer could depend on how much of the arbitrage is due to lack of fluid information flow (information arbitrage) and misinterpretation of business risk factors compared to how much is due to behavior, regulation and environmental factors shaping attitudes about overall risk aversion and appetite for certain asset classes. I would argue that it’s quite efficient that, over the long-term, some factors should allow growth at a reasonable price (“GARP”) microcaps to exceed the returns of the market or large caps.

These two forces work together to give you opportunities and to determine how long it takes the market to reward you for your hard research.

How is it be possible to buy Evans & Sutherland (OOTC:ESCC) at valuations ($0.14 in 2014) indicating bankruptcy when SEC filings clearly indicated that liquidity issues would be favorably resolved well ahead of its huge multi-bagger move to $1.98; or to buy Zynex Inc (OOTC:ZYXI) ($0.40 in 2017) weeks before it began its monster move to $5.50, when press releases had been clearly indicating sustained profitability and de-risking balance sheet moves?

The inefficiencies in the microcap universe provide tremendous information arbitrage chances. It makes perfect sense that information arbitrage and gaining a better understanding of a company’s growth and risk profile than your peers exploits the “inefficiencies” of the EMH. It’s also clear that the less participation by investors in the microcap space compared to large caps helps create this opportunity. This “lack of participation” has always been a factor. But how much of the alpha is from inefficiencies.

Maybe, what is efficient, is how behavior changes over time to add to or subtract from the pool of microcap investors and impact their attitude towards related stocks, thus influencing how long it takes for stocks to react to positive developments and investors’ required rates of return.

Before 2008, I would have told you that prices would adjust upward to the information arbitrage identified through great GARP research in a reasonable time frame, once the market found vital information. In essence, enough inefficiency existed to give you time to buy stocks early, but eventually, enough market interest (efficiency) would build to allow you to earn a nice return on your research in a reasonable amount of time. At times, I would hold of hundreds of stocks, Peter Lynch style, and easily beat the market.

Since the Global Recession, it has been my observation that the performance of quality GARP microcaps have often underperformed speculative “get rich quick” microcaps and their larger counterparts. My biggest takeaway is that it has been taking longer for these GARP stocks to rise to fair valuations. How is it possible that it takes longer to be rewarded for your good research, when information is more available than it has even been?

The answer takes me back to a presentation I had the pleasure of giving at Fred Rockwell’s microcap conference event on April 11, 2016 in Toronto that could tie neatly into Professor Lo’s logic. The global recession has, no doubt, impacted the way investors act and react in the stock market.

Reduction in Pool of Investors:

- Many microcap investors disappeared from the market and/or never came back to invest in microcaps.

- The rise of ETFs and passive investing has reduced the number of investors using stock picking as a strategy, a dagger in the heart to microcaps.

- ETFs typically are not investing in true microcaps (market cap less than $300 million).

Changing Attitudes to Risk:

- Some investors don’t want to deal with the perceived risk inherent in microcaps, so they think they can take less risk in large caps.

- Large cap returns have been sufficient (due to Fed policies) to keep investors satisfied

- Investors don’t want to hold stocks long-term (holding period of retail investors has gone from 6 years to 6 months).

- Aversion to time, ironically, has investors looking for highly speculative (non-GARP) microcap plays like biotechs and pump and dumps to make big money fast.

These trends are both good news and bad news. It’s great to be able to buy all the stock you want of some really undervalued names, but there is a price to pay other than dollars and cents. GARP investors have needed to wait longer to get paid. If you are a long-term investor, you might not be phased, but if you have been spoiled to be accustomed to achieving quick returns, then you may have felt a high level of frustration for the last 10 years or so. As for me, my behavior has changed in a few ways. I am “adapting” to be a more patient, longer-term investor, and employ a more concentrated investment style. Because I know I may need to be invested longer in some of my stocks, I take deeper dives into their stories, which I think has made me a better investor.

Conclusion

The pendulum swings both ways. The time it takes for many GARP microcap stocks to reflect their true value is taking longer than other cycles I have gone through, but GARP investors are finally beginning to get paid sooner.

Overall, I think examining the EMH is an interesting exercise, but reality will often diverge from hypothesizes and theories. One thing is for certain: information arbitrage chances in the microcap world are both real and widely present, and wont’t change anytime soon.