Active vs Passive investing strategy is a hot topic of discussion within the investment community. Passive investment strategies such as the classical market-weighted indexing are gaining in popularity. Since John Bogle started The Vanguard Group in 1974, its assets have grown so substantially that index funds are forecasted to surpass actively managed funds by 2024 according to Moody’s Investor Services.

Vanguard’s John Bogle is praised by Warren Buffett and others as a savior of the system, and there is a case to be made that the index system has left billions of dollars in the pockets of retail investors instead of Wall Street agents. Buffett, a stock picker himself, has also taken a public bet against active management, which he seems to be winning for a variety of reasons. We here at GeoInvesting see this as an opportunity to test our philosophies.

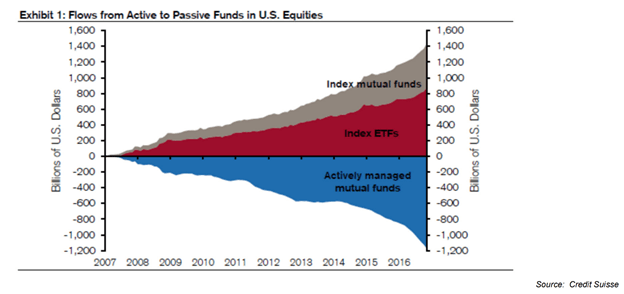

Recent discussions surrounding active management have focused on the 2-20 fee model (which barely exists anymore) for hedge funds and many LPs demand lower fees for active management. The flow into passive strategies has been rapid and seems to be accelerating.

But what do “active” and “passive” actually mean? There are conflating definitions and, as we will uncover, they mean very different things.

What are the implications of this shift to passive investing, especially for active money managers? Make no mistake about it, if you are an active money manager, especially with sizable assets, passive strategies pose a terrible problem for you because they simply seem to be (and probably are) a better alternative for your clients. This article is an attempt, from an active manager’s point of view, to study the opponent’s patterns and position for outperformance.

The Passive Investing Players

Passive investment strategies come in many forms and can be employed using many different vehicles. Definitions of “passive investments” differ. For example, Investopedia defines passive investing in a much broader sense than Wikipedia, and passive is sometimes equated to “low portfolio turnover” or “buy and hold”. Often times it is arguable if a quantitative strategy is active or passive, and it might be tough to draw a line. Shockingly, many discussions on active vs passive management do not even bother to define the terms. Clearly, the terms have to be defined before a sensible discussion can take place. A sensible definition has to focus on the process by which decisions are made, rather than derivatives of the process, such as trading pace and costs.

When you narrow it down, there are really two ways to contrast active and passive investing and they don’t conceptually overlap. At first, it might be useful to separate them before looking at them in combination.

One could say that passive investing is:

“An investment strategy that attempts to reflect a chosen market’s return on a risk-adjusted basis.”

In contrast to active investing:

“An investment strategy that attempts to achieve better risk-adjusted returns than a benchmark or does not have a benchmark.”

On the other hand, quite literally interpreted, passive investing can be defined as:

“An investment strategy that attempts to minimize costs.”

In contrast to:

“An investment strategy that incurs a lot of costs.”

What is the right definition, and can we combine these two perspectives? We will find out that the first aspect laid ground for passive investing strategies, but the secret to net outperformance might lay in the latter.

While the first definition is general and should always be applicable, the second definition is really a derivative of the trade-offs that passive investment strategies have to make when aspiring to replicate a market’s performance. We will find that the two ideas actually have offsetting forces. For the purposes of this article, we apply the first definition and passive investing to index investing.

Active Managers as a Group Never Had a Chance against the Indices

- “Active managers have underperformed their benchmark index in three out of the last 5 years.”

- “Alpha in active management is cyclical”

- “Active managers navigate value regimes better than growth regimes”

The three statements above are examples of a lot of the discussion currently surrounding active and passive management. One does not have to think hard to reveal these statements as either based on imprecise definitions, bad measurement, or just a lack of understanding of basic arithmetic.

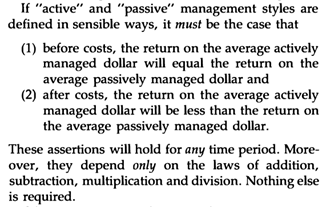

William Sharpe amply explains an often overlooked, but simple fact about active and passive management in his 1991 paper “The Arithmetic of Active Management”.

Of course, this idea is extremely normative and has several challenges in reality, which should give hope to the active investment community and might give some credibility to the three statements above (although I am not sure their authors understand this). First of all, there needs to be one market in which participants act. In reality, even public markets are hugely fragmented into different securities, market capitalization, nations, and there is not a market weighted index for all global securities.

Second, the idea only holds valid if passive investors are able to hold each security in the manner as the market. For instance, if a security represents 3% of the market capitalization of the market at any given moment, passive investors will have 3% of their portfolio invested in this security. In practice, there is an implementation shortfall and perfect replication is not possible in a market where trading costs still exist. These, among other factors, might explain the results of several studies on active vs. passive management that seem to violate the basic laws of arithmetic. Mostly, I think these studies are simply based on bad definitions of active and passive, incomplete data, often mixed with a clear research bias. In short, they are useless to the serious practitioner.

Despite being normative, William Sharpe’s insight generally holds true, especially in regard to money managers operating in efficient, heavily trafficked markets like the S&P. In aggregate, after fees, active managers will be losing to passive market weighted investment funds. Other less efficient markets such as the microcap market that GeoInvesting focuses on are less so because of less information.

Note, however, that in order for this statement to hold true, passive managers need to ensure two things: (1) do a decent job replicating the benchmark and (2) don’t incur meaningful frictional costs along the way that would make net performance suffer. This is in insight we will revisit later as they might give a clue to beating passive managers. Frictional costs include all kinds of costs that a fund incurs to get its desired portfolio, including research costs, trading costs, and all costs related to maintaining the infrastructure and paying the staff.

Sharpe’s idea is not only applicable to classic market index funds, but also to any tracking strategy. If, for example, a hedge fund index that tracks a certain group of funds was able to hold any given security in the same proportion as the hedge funds as a group, then by definition the index would receive, before fees, the same returns as the hedge fund group. Because the index will charge lower fees, the active managers will lose net of fees to their index. Again, several practical challenges, such as the replication problem and frictional costs, are associated with this idea.

Index funds allowed the public to participate in the stock market in a low-cost way. They add benefit to the individual, but does it add benefit to the system? I find this to be arguable.

Markets need actively choosing participants to function

The public markets for securities exist primarily to allocate capital to deserving companies. Investors get to share the risk of a company and demand adequate returns. Companies that have sensible extension projects can raise capital at sensible prices. Pricing plays in important role in this system. Pricing allows capital to be adequately allocated among companies.

In order to price something, you need participants with an opinion. Index funds are the worst from this perspective, as they are the ultimate sheep, passively following the market/underlying in whatever direction it moves. If the market irrationally bids up the market capitalization of fraudulent companies, the index investors will follow. The price is the holy signal of the market-weighted index fund, and it will adhere to whatever signal the price sends. One could argue that even though index funds have a dampening effect on the market, as they are delayed in their trading, they ultimately exaggerate major market moves because they are forced by their guidelines to adjust positions regardless of underlying economic reality.

Index funds have also shown to be rather passive when it comes to pushing towards corporate changes.

Most ETF’s and self-proclaimed “passive-strategies” mimic some other aspect of active management. They are, in consequence, replications of these active strategies with the standard deviations from implementation issues. They do not really think that much or provide much in terms of pricing efficiency and they are also followers of the active management ideas.

While the average passively invested dollar is likely to do better after fees than the average invested active dollar in the same market, from a pricing perspective, index funds provide little benefit to the system.

Pricing a Public Good

Recall a lesson from your basic economics course. What do you call a good with these two properties?

- Anyone can have it without taking it from others

- No one can be excluded from having it.

The answer: A public good.

Prices for publicly traded securities fulfill these two requirements. Normally public goods are provided, or at least maintained to some degree by the government, while public prices are not. The “right” prices for securities are discovered by the hard-working analysts and portfolio managers who dig into a company to understand it thoroughly. These participants who expend resources to act on their conclusions are what makes the market work in the first place.

I argue that index investors are nothing but free-riders, coasting on the work of others. Consequentially, the fair way to regulate the market and give the right incentive might be to impose a special tax on passive investors, or grant tax cuts of some sort to active participants who contribute to price discovery.

Yes, Jack Bogle might be right when he says that stock picking as a whole is a “loser’s game”, but he free-rides on the pricing provided by the very same people.

You get what you pay for

The “you get what you pay for” idea might not be applicable to the individual investor, who should probably try to keep his fees low, but rather to the system. The individual gains an extremely helpful, and low-cost vehicle to participate in the public markets with the emergence of market-weighted index funds.

At the same time, the more resources you spend on forming an opinion on the value of a security, the better you will be able to price this security. While the relationship is certainly not linear, the more resources the market as a whole expends, the more efficient the price discovery process should be.

Passive Investing — The Reality

In practice, index investing is a lot more active than described in Sharpe’s model. First of all, passive managers have to pick their market and their asset class. This article does a good job explaining how passive investing strategies actually require a lot of active management choices.

The two biggest choices in passive management are:

(1) What market to track

(2) How to go about tracking the market

The first choice does not have great implications on Sharpe’s view on active vs passive management due to the assumption of an efficient market. Within a defined market, the active managers who incur more costs as a group will be beaten net of fees by the passive managers.

Note that Sharpe’s arithmetic is only valid if the passive managers, in aggregate, are able to hold any given security in the same proportion to their portfolio as the active manager group. This leads to the second big issue in passive management, which is how to go about tracking the chosen market – not always a straight forward task. Imagine an index fund was trying to hold any given security in the exact proportion as the market at any given time. That would lead require incredible amounts of transactions, and consequentially big transaction costs that would render this effort infeasible. Note that this basically renders a combination of the two definitions of passive investing that we looked at in the beginning of this article completely counterintuitive.

In this trade-off between trying to replicate a market perfectly, and incurring frictional costs, lay many answers and implications for active investors. We should take a closer look at how this tracking process works. While many indices nowadays try to replicate a market’s performance via derivatives, most still buy securities directly. By definition, index investors will always be the followers. An index buys and sells according to the buying and selling that active market participants have already done. The intuitive conclusion would be that this is an advantage for active investors as they are literally “ahead” of the passive investors and can react to significant developments more quickly. Strangely, rebalancing poses a problem for index investors from this perspective and there seems to be no obvious systematic advantages to a big tracking difference.

Active vs Passive Investing – Why do Passive Investment Managers Still Outperform their Active Counterparts?

If you are looking for a straight forward answer, I will have to disappoint you. It turns out to be a multitude of factors that are intermingled.

The first important factor concerns fees, and passively managed vehicles being able to charge their clients less because the infrastructure is ultimately cheaper.

The second important aspect, however, has to do with the way passive investors track benchmarks, but the drivers of the outperformance are not directly visible and hard to isolate. Again, the tracking of benchmarks involves two problems (1) replicating the desired benchmark accurately, and (2) don’t incur meaningful frictional costs along the way that would make net performance suffer.

Replication Problem — Is Being Late to the Trade Good?

The problem arising from being able to replicate a benchmark portfolio perfectly does not lend itself to a clear advantage for passive investors. Certainly, passive investors can’t replicate the benchmark perfectly because, as we explained before, it would incur unbearable trading costs. So, the question is: Do passive funds get real alpha through the deviation from their benchmarks? In different words: is it an advantage to get in late on every trade? How late do you want to be? I have not seen conclusive studies on this question and the intuition is that if you trade on a meaningful insight, being late to a trade will be a disadvantage.

At the same time, we know that people trade, most of the time, on meaningless insights. In his 1995 highly insightful paper “The Only Game in Town”, Jack Treynor shows how people evidently trade too much on what they perceive to be a meaningful insight, which in reality is not the case.

Keep Costs low — Why do Passive Managers Trade Less?

The cost problem gives an advantage to passive managers, because they spend less money on research, infrastructure and overhead, but it is worthwhile to isolate trading costs from the other frictional costs here. As explained, there is a tradeoff between replicating the portfolio and high trading costs, but the big index funds show turnover ratios below 5% p.a., while data suggests that hedge funds are in the 30% plus range. Herein lies the cost problem and replication problem becoming intermingled in trading costs. It is not clear to me why active managers have to trade a lot more than passive investors as a whole.

Implications for Active Managers

What is the right way to react to these developments from the perspective of a fundamental stock picker? Rather unsurprisingly, the questions of how to beat the index fund and how to beat the market are very similar. These are just are few suggestions that are not meant to be a formula that works for everybody. Doing the opposite of the proposed strategy might often times work as well.

Avoid heavily trafficked markets

Try to avoid participating in highly trafficked markets like the S&P with high liquidity, where the index fund is likely to be a better alternative to active management. In the end, active managers will be spending a lot of time and money on price discovery that passive players can rather easily take advantage off while incurring lower costs. Also, with everybody looking at the same stocks it is hard to get an edge. Why would you compete against Warren Buffett for the same opportunities if you can choose not to do so?

This is one reason why GeoInvesting has chosen to focus on the thinly traded, often ignored micro cap market.

Don’t diversify too much

It doesn’t matter how you arrive at it, if you hold a portfolio that looks very similar to the index it will be unlikely that you outperform meaningfully. While the idea of diversification is praised in finance academia, I find Charlie Munger’s statement more intuitive: “Investing is looking for situations when it is smart not to diversify”, and many notable investors seem to agree.

Trade less

Why do index funds have a meaningfully lower turnover ratio than active funds? Intuition tells you that if active investors were really buying on the basis of meaningful insights, passive investors would see major performance drag due to them having to lag the active managers’ trading. We have to acknowledge that people obviously trade on a lot of meaningless information and there seems to be an entertainment value to trading. Several academic studies and papers elaborate on that point.

What should active managers do? The way to act is obviously to pay close attention to trading costs and try to reduce turnover meaningfully. The temptation to act is strong, but the winning formula should include doing nothing for a long time and only acting when you have meaningful insights and real conviction. This video series shows Charlie Munger talking about how he exercised extreme patience and claims to have read Barron’s for 60 years to find one good investment that made it all worthwhile. This strategy will naturally lead to a portfolio of few securities and does not lend itself to great diversification.

Be specialized, have an edge

The strategy you pursue should be hard to copy and that probably means that you occupy a niche where you have developed superior expertise, infrastructure, and reputation. Maybe you specialize on finding accounting fraud in obscure, overlooked securities. Whatever it might be, it should not be easy for everyone to copy and achieve the same returns without incurring great costs and effort.

Closely related to that idea is the competitive edge, and you certainly want to have one. In this article I talk a little bit more about different kind of edges. You want to have an edge that is at best sustainable and defendable, permanent capital and reputation are good examples of a defendable competitive edge.

Be Patient, Seek Position Instead of Attack

Index funds seem to have encountered only modest problems from the rebalancing issue, but that does not mean that this will always be the case. I can imagine a few scenarios, in which meaningfully big index positions fall rapidly and index funds would be unable to rebalance adequately and only delay and then later amplify the race to the bottom.

It seems to be a good idea to spend thought on scenarios where the rebalancing issue can be exploited and how to go about it.

Be Adaptable, Learn and Evolve your Strategy

The last idea that I really like is the distaste for the stagnant. In my view a good investor should continuously learn, study, and evolve the strategy without making changes for the sake of changes.

No edge is long term sustainable if you don’t work on it and try to build it out. Some edges might turn out to be not scalable and one has to completely change the strategy. The market is competitive and if you are getting extraordinary results, other people will see it and try to copy you. If you are stagnant, competitors are sure to catch up and eventually pass by.

Conclusion

Bottom line, it could be possible for active managers as a group to outperform the index managers even within a defined market, because it is impossible for the index managers as a group to always hold the exact same stocks as the active managers. However, it seems like that active managers will have to overcome the issue of higher costs, and have to make the index’s rebalancing issue work to their advantage. As a group, it seems unlikely that active managers will find ways to be as cost effective as an index fund or trade more efficiently. The success of index funds painfully points out failures of the active management community.

The tactics described here can help active managers avoid being replaced by an index and stay competitive, especially in the inefficient markets. Not surprisingly, the methods to compete against passive managers are overlapping with many general themes on how to compete.

The other question is how indexing influences our system overall. Index funds don’t really contribute to the price discovery process and are “free riders”. In fact, they might even be harmful because they exaggerate market moves and buy and sell — many times with leverage – without any consideration for real underlying economic reality. Therefore, the right way to regulate is to give incentive to active investors and/or punish index investors, something that smaller, nimbler organizations can exploit.

I agree that index funds have added great benefit to the individual investors and that there is a place for them in the market. At the same time, it seems to me that the concept of “an increasing proportion of the market that blindly follows the rest in what they do” is a recipe for exaggeration, bubbles, and ultimately disaster. Opportunity for active investors such as GeoInvesting.

Evan

Thanks for the article.

“It doesn’t matter how you arrive at it, if you hold a portfolio that looks very similar to the index it will be unlikely that you outperform meaningfully. While the idea of diversification is praised in finance academia, I find Charlie Munger’s statement more intuitive: ‘Investing is looking for situations when it is smart not to diversify’, and many notable investors seem to agree.”

This really depends on the type of strategy that you’re pursuing. You won’t invest in the entire index for any active strategy but some require much wider diversification than others. For example, you can leverage the great statistical performance of deep value strategies often require fairly wide diversification. This sort of deep value investing is somewhat like building your own “index” of stocks that fit specific metrics, such as no debt and very low price to book. You would then look at the outcome of the group rather than specific stocks. This is a very lucrative strategy.

“The strategy you pursue should be hard to copy and that probably means that you occupy a niche where you have developed superior expertise, infrastructure, and reputation. Maybe you specialize on finding accounting fraud in obscure, overlooked securities. Whatever it might be, it should not be easy for everyone to copy and achieve the same returns without incurring great costs and effort.”

Investors managing a portfolio of less than $1 million have a built in competitive advantage – they can take advantage of the best stocks among companies with the lowest market caps and lowest liquidity. This is a major advantage because the professionals can’t buy these firms due to the amount of money they have to manage. Returns to deep value stocks below the $100 million USD mark in market cap produce some of the best returns available to any investor.

Evan,

Thanks for your interesting comment and sorry for not getting back to you right away. Things heating up over here.

I wholeheartedly agree with your comments. Opportunities (and especially the best opportunities) are limited in absolute size and as an asset manager you have a certain amount of capital to employ. So there is a trade off.

Statistical arbitrage, factor investing, make sense to me and I think are sensible strategies to consider as assets grow. The data supports your point that value investing works over long periods of time.

There is one more idea I would add. Factor investing and statistical arbitrage mostly concentrate on isolated factors and signals like P/B, P/E, etc. They barely observe the value drivers directly and don’t really observe in context. Rules based investing of the kind you mention certainly brings about discipline and there is a strong case to be made for it. I simply want to caution that a P/E ratio is only as good as the accounting and I worry very much about distortions in this regard.