Introduction (3:32)

I want to first start by Thanking the Museum of American Finance for inviting me here today and organizing this event and of course the Gabelli School of Business for co-hosting and sponsoring this. It is a great pleasure and privilege for me to be here because in a way I am a product of American Finance.

In fact, when I first came across the title of the Museum, I was convinced that it was a typo and that it was meant to be the “American Museum of Finance” as opposed to the Museum of American Finance.

But the Fact is that actually there is a uniquely “American form of Finance” and all of you, I suspect, know that Alexander Hamilton played a pretty critical role in creating that new form of finance. In fact, I think Richard and David have a book coming out on Alexander Hamilton that’s a must read.

So, it is very appropriate that this is an event for me, because I really do feel beholding to that system, that framework that gave me the opportunity to be here today and to be in the career that I am. I am also particularly grateful to be here at Fordham University because I actually grew up in New York City. I migrated to United Started when I was 5 years old, went to public schools throughout, went to High school at Bronx at the Bronx High School of Science and Fordham University, at the time was just in the Bronx and it was a mainstay of many students and a number of the High School students, made their way over to Fordham and number of the college students came by and mentored us and it is wonderful to see how Fordham has grown and spread and has succeeded over the course of last just few years. So, I am really happy to be talking about my book also because there are some really interesting connections between adaptive markets and value investing and what all of you are doing here.

I also want to thank the folks online for joining and Bloomberg for Sponsoring this event. I am hoping that you will see the various different connections not only with Finance, but with broader areas learning and I am going to try to draw that out over the course of the next half an hour or so.

Motivation on For the Book

Let me begin by telling a little bit about why I wrote the book. It wasn’t really planned. In fact, for those of you who have a copy of the book, I need to first apologize immediately for its length. I generally don’t go on and on, but my publisher told me something before I handed in the manuscript. He said that “remember Andrew, every equation you include in the book, will reduce your readership by 50%.”. So, I took that to heart and there is not a single equation in the book. As a result, its 500 pages long. So, I apologize but the reason that it ended up being that length is because it’s a chronicle of my own journey and frustration with the state of affairs that even today still affects financial economics. And the state of affairs, I suspect most of you know, is the fact that most of us who grew up in this kind of a “Neoclassical financial economics” type of a paradigm, were taught the Efficient Market Hypothesis.

The idea that prices fully and everywhere and always reflect all available information. And at the opposite end of that spectrum is the fact that people are people and we engage in all sorts of human biases foibles and irrationalities.

There is a pretty wide gulf between these two schools of thought and as a graduate student, I was introduced to both of them and it was really difficult to choose. You know, it’s kind of like a child listening to his or her parents arguing, you know, you just want to stop and get along and you know that they love each other, but they just you know can’t come to terms. So, I decided over the course of probably now going on 25 years to try to reconcile these two warring parties and that is really the nature of this book.

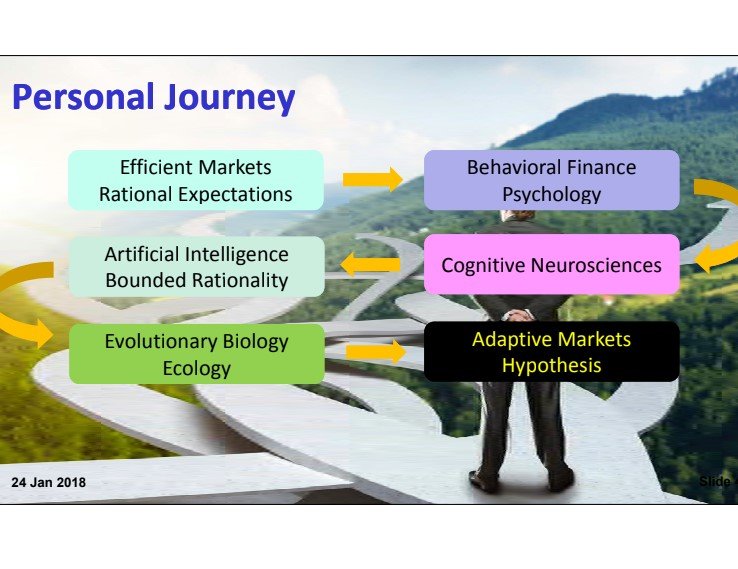

What I wanted to do was to describe the different paths that I have ended up taking to try to reconcile these two schools of thoughts and really that path started off as a graduate student when I started reading a lot of the psychology literature. Like many of you I began with the idea that markets are efficient, people behave in a rational manner and from that literature, I was brought to the psychology literature that showed all sorts of experiments, behavioural economics, behavioural finance that demonstrated that people did not react in the ways that we would predict using expectation of mere utility functions and so on. And so that digression to behavioural finance and psychology, naturally brought me to the cognitive neurosciences that of course brought me then to artificial intelligence and the theory of bounded rationality, which eventually brought me to evolutionary biology and ecology and ultimately when you synthesize all these various different schools of thought, you get what I call for lack of better term “The Adaptive Market Hypothesis”.

So, with your permission what I am going to do is to take you through a little bit of the meandering path, but that is really what the 500 pages consists of. It consists of my own personal journey through these various different literatures, because I think like you I started out being a great sceptic of behaviour and how all of these pieces might fit together in some kind of a framework.

So, that is where we are going and let me just give you a quick summary. Ultimately, what I am going to do is to reconcile these two fighting parents and show you that there is a framework that allows us to think about both behaviour and rational deliberation in the same breath.

Quick Glance at The Adaptive Market Hypothesis

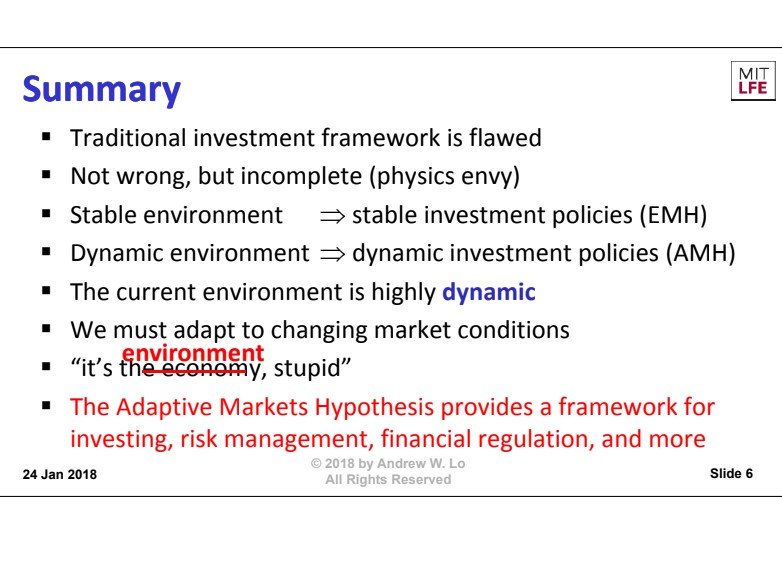

And so here is the quick summary. The Adaptive Market Hypothesis begins with the acknowledgement that the traditional paradigm of investment analysis, what we know and love and use in our day-to-day practices is not wrong, but its incomplete. It doesn’t capture the fact that in a very dynamic environment, we are not going to see the same king of relationships as in the static environment. So, when the things are stable, then stable investment policies make sense.

But when things are highly dynamic, well then actually things don’t stay the same and people adapt to those kinds of changes and the fact is that right now we are living a very dynamic economy with lots of things changing even day-to-day and so the reason that many of these theories look like they are not working is not because they are wrong, but because they are not being applied to the right context and we need a meta theory to allow us to integrate all of these ideas.

That is the idea behind the Adaptive Markets Hypothesis.

You know that we all say that it’s the “economy stupid politicians’ that have been saying for years that drives political events. Well, what I think that evolutionary biologists should start telling economists, you know what, it’s the environment that actually drives all of these various different kinds of behaviours and so what I am going to try to do in the next half hour or so is to give you by way of a few examples how it is that this new framework allows us to integrate, what we know and love the traditional investment framework with all of the various anomalies that is becoming harder and harder to ignore.

So, in order to do that, I want to start with the traditional investment framework

and that investment framework really has to do with a creation myth that we finance professors more than anybody else perpetrate on our students and the myth goes like this.

The Efficient Market Hypothesis

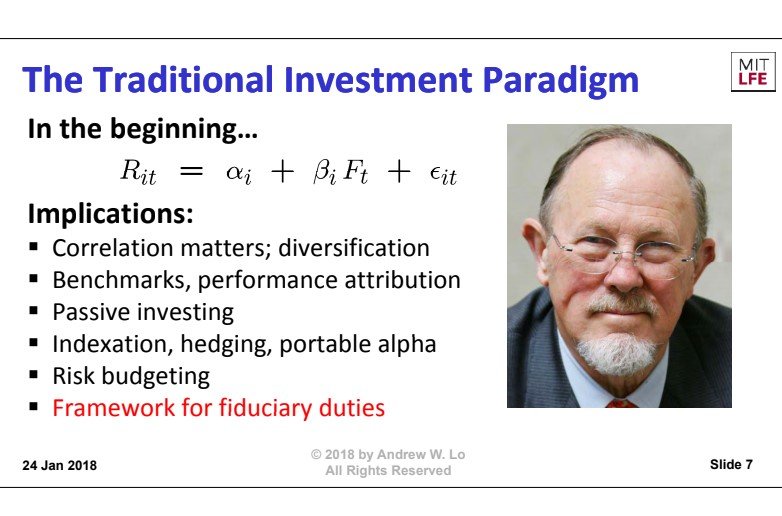

In the beginning and by the beginning I mean 1964, in the beginning Will Sharpe said “Let there be Beta” and there was beta and that was good.

This framework, a single facto model that allows us to price systematic risk and separate that from unique investment acumen namely “Alpha”, gave us all sorts of opportunities to create new financial products and services. Most importantly though, it allowed us to discharge our fiduciary duties to our clients by giving us a rational framework for thinking about how to invest. It democratized finance for the masses, a very important innovation.

Now this innovation didn’t come free. There was a cost and in particular the cost was a set of assumptions. We had to make some assumptions in order to generate that kind of a simple linear relationship between risk and reward. And what are those assumptions? Well, we had to assume that the relationship between risk and reward is linear. We had to assume that the parameters were stable over time and space and that we could estimate them and be able to make use of them and most importantly, we had to assume that markets were rational, that people were efficient in how they priced these kinds of risks.

What if it is the case that some of these assumptions don’t hold? Well, it turns out that if any one of these assumptions is violated, you do not get the simple “risk-reward relationship”. It gets more complicated and, in some cases, when some of these assumptions are violated at the same time you don’t get anything that looks even closely like the kind of a “risk-reward relationship” that we used in practice.

Now, I have to say that again the framework is not wrong. All economic theories are meant to be approximations to a much more complex reality and so these question really is how good is the approximation, how large are the approximation errors? And so the first thing I want to point out is that this framework that we all know and love, don’t worry you don’t need to throw it out, because it turns out that for a very long time, this was an excellent approximation to much more complicated reality and to illustrate that

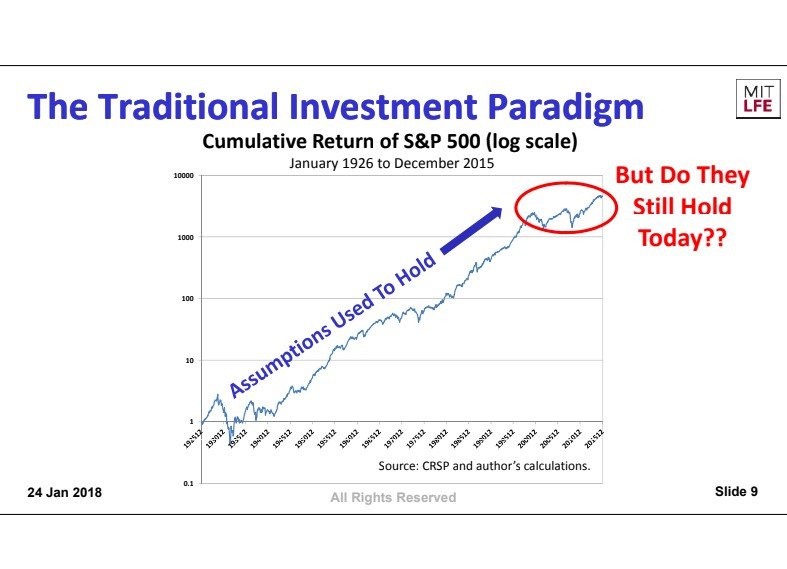

I am going to show you this graph that probably looks unfamiliar to you, but every single one of you, I suspect has already seen this graph. You just don’t know it.

This is a graph of the cumulative performance over $1 investment in the S&P 5000 from 1926 to the present.

Now the reason you don’t recognize this, it is because I have plotted it on a semi logarithmic scale and the reason I did that was because on a log scale, it turns out that equal vertical distances correspond to equal rates of return and so if you have got an investment that has roughly the same rate of return over the time, it looks like a straight line on this graph and when you look at this graph, you see that the United States Stock market has been one of the most consistent investment in the history of capital markets . For a period of about five or six decades, the US stock market looks like a straight line. It turns out that during this period, the assumptions that I showed you on the previous page were an excellent approximation to this much more complicated reality. Does not much matter where you invest during that period of the 1930’s to the early 2000’s, you would have earned approximately a risk premium of about 8% with an approximate standard deviation of about 15-20 %. Pretty reliable risk reward trade-off during that period of time.

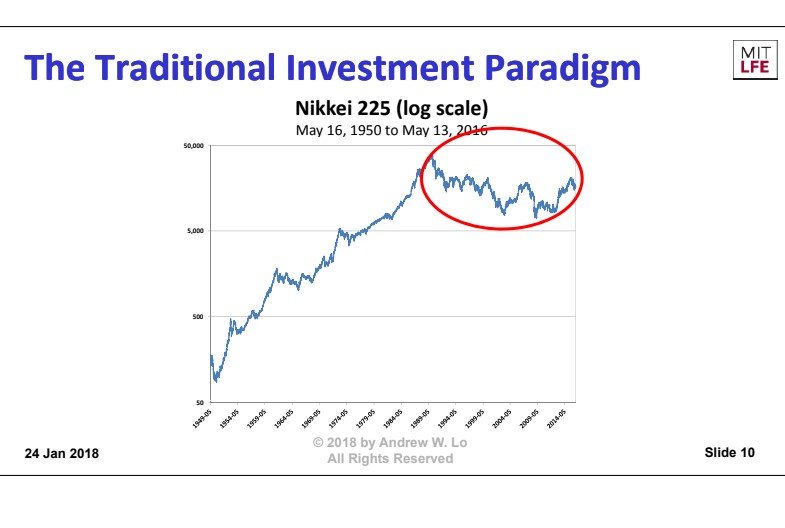

But take a look at the last 15 years. Do you believe that the last 15 years is just like the previous 50? If you do then you don’t need any other theories, the traditional efficient markets hypothesis, Cap M and all of the various different implications are just fine. But I would argue that the last 15 or 20 years, it does look a little bit different and there are reasons that I will give you in a few minutes why I think there are very different. And in case you want to see a better example of this kind of a difference, let me show you Japan. So, this is the Japanese stock market form 1940’s to the present.

They also had their period of about 20 or 30 years of very, very stable performance in the Japanese stock market. But starting in the 1980’s, they ran into a problem, as I am sure all of you know, and the lost decade became the lost two decades and now we are running on the lost three decades in Japan. So once again, you look at this and you ask yourself well do you think that the last 30 years was just a minor blip in an otherwise upward trending curve or did something change? I would argue that something has changed and so the adaptive market Hypothesis takes change seriously and asks the question, what are you going to do about that change. How are you going to respond? How will you adapt to that change?

So the basic idea behind the Adaptive Market Hypothesis really follows that of evolutionary biology and the great evolutionary biologist Theodosius Dobzhansky once said that nothing in biology makes sense except in the light of evolution and so I am going to steal his phrase and repurpose it for our current context, which is that nothing in the financial industry makes sense expect in the light of adaptive markets and I am going to try and convince you of that by giving you some examples.

First of all, before we go on let me define what I mean by adaptive markets.

These are some very basic principles that are outlined in the book about what adaptive markets is. We start with the assumption that people act in their own self-interest. I think that most economists would agree with that statement. But starting from that point onwards, we depart from the traditional economics theories because we are going to acknowledge that we make mistakes. We are not perfect and we don’t engage in rational expectations. We suffer from all sorts of behavioural biases. However, we learn and adapt from those mistakes and it is that adaptation and the process of natural selection that ultimately governs markets dynamics. So, it’s really evolutionary theory applied to financial markets. And when I say applied, I don’t mean as a metaphor or as an analogy. I mean literally it is a part of evolutionary biology and we are all animals and it turns out that one of the ways that we have adapted to dealing with an otherwise hostile environment is capital markets. That’s a tool that we use, just like the opposable thumb. I am going to you some examples of that and then I am looking forward to the discussion.

Human Behavior

I am sure that it is going to be by far the most unlikely portion of this evening to get your comments and reactions to this. So, I want to first start by describing a little bit about human behaviour and particularly I want to talk about what investors really want. I suspect many of you already know that and if you have seen this example before, please don’t give it away to the rest of the audience.

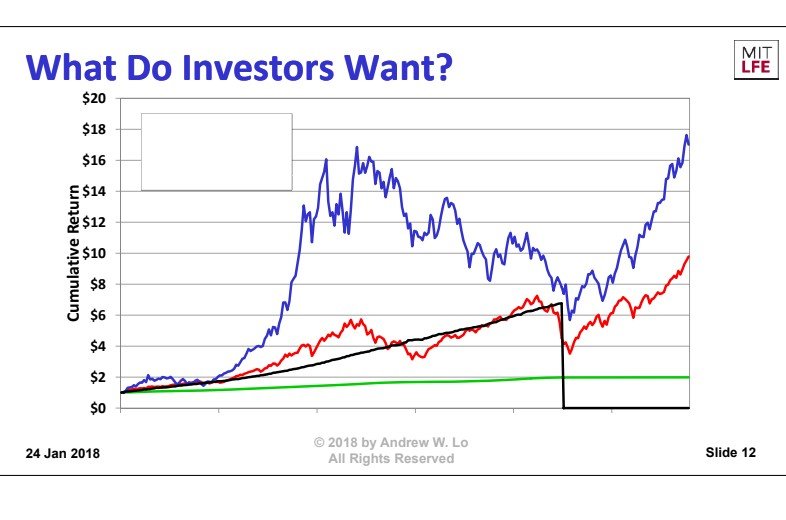

I am going to show you four financial investments. I am not going to tell you what they are. I am not even going to tell you over what time period they span. I am simply going to show you the cumulative performance of over one-dollar investment in each of these four assets and I am going to ask you to pick one of these four for your retirement portfolio or for your parents or grandparents retirement portfolios.

Let me show you what they are.

We have got the Green line, Blue Line, Red Line and the Black Line and you see they all started out at a dollar, but they have very, very different risk reward characteristic.

The green line goes from $1 to $2. Not very interesting, although you don’t even know what the investment period it is. I am going to tell you that these are a matter of many years now. This is not days or weeks. Its years that we are talking about. And so, the green line is not all that interesting, but it’s also not nearly as volatile as say… The red line turns a dollar into about four and a half, but way more ups and downs. The blue line is even more profitable, but also quite a bit more volatile and the black line is somewhere in the middle. So, this is all about your own personal risk preferences. What would you like for your retirement portfolio, if you could have one and only one, you can’t mix and match these.

So, how many people by a show of hands would want the green investment? One person for the green investment. Okay, how about the red investment. Anybody want the red investment? Wow, nobody wants the red?

So, I want you all to remember this moment, because after I tell you what it is you are going have some rethinking to do. Right? Alright.

How about the blue investment? How many people want the blue investment? Okay, wow we got the hedge fund managers that came out tonight and now how about the black investment?

Yeah, so in all of the audiences that I have presented this to that is by far the most popular investment, because it has got seemingly the most attractive trade-off between risk and reward.

Well, let me tell you what these four investments are. First of all, the time period that we are talking about is 1990 to 2008. So, that is the time period and the four investments are these:

The green line is US treasury bills, the safest asset in the world that at least until Feb 6th, but not very interesting from a performance perspective. You are not going to make a lot of money, so probably not a great thing to invest in for retirement unless you are way past retirement and looking really to preserve wealth.

Now, what about the red line that none of your picked. You know what that is? The red line is the S&P 500. Most of you already have investments in that, so you need to start rebalancing your portfolio now after this. But, you can see that’s more volatile, but actually you would have done well had you put your money in S&P in 2008.

The blue line is the single stock Pfizer (NYSE:PFE), the pharmaceutical company, way more volatile, but also has done very well since 2008.

Now, what about the most popular investment, the asset that all of you picked. Well, this is the returns to a private fund called the Fairfield century fund. This for those of you who are hedge fund aficionados was the feeder fund for the Bernie made of Ponzi scheme. Which is why I had to stop it in 2008.

Now you know how the Ponzi scheme got as big as it did. It’s Human nature. We are all drawn like a moth to a flame. We are drawn to investments with high yield and low risk. Right? High Sharpe ratios and in many cases that gets us into trouble. It is Human nature.

The Peltzman Effect

But, it is more complicated than this, you know because we actually adapt to changing perceived risk and I want to show you an illustration of that from a very, very old academic study.

It was done in 1975 by a University of Chicago economist by the name of Sam Peltzman. So, this might sound like a very boring title, “The effects of automobile safety regulation”, but this is one of the most exciting papers in the history of the economics literature and I will tell you why.

In 1975, Peltzman being a good Chicago economist that he was, decided to ask the question. How much value has government created in mandating all of those automobile safety regulations? Because ultimately those costs are passed on to the consumer. So, we end up paying for those costs. Things like reinforced bumpers, padded dashboards, collapsible steering column, seat belts, lap belts so on and so forth. Every one of these safety regulations that was mandated by law so that all automobile manufactures had to install them, ultimately raised the prices of these cars and we paid for them. So, the natural question that he asked, was okay well fine. We are going to pay for them, but what is the benefit? How many lives have been saved by all of these mandated safety regulations? So, he decided to look. He looked at the number of Highway deaths before, during and after these pieces of legislations and what he had found was absolutely shocking. He found that there were no lives saved, none, with all of these safety regulations. Now, that is not exactly right. But what he found was that initially right after the safety regulations were imposed, the number of deaths from traffic accidents did decline and then after a few years then it went right back up to where it was before.

In fact, there was only one instance where he found that it looked like there was a relatively permanent decline in the number of automobile occupant deaths and the reason I put it in those terms was because in that instance, he found that those decreases in deaths were offset by increases in the number of pedestrian deaths. So, what he concluded is that every time one of these safety regulations was imposed, initially it reduced the number of deaths and then people adapted because there were driving safer cars they simply drove faster and more recklessly and so his conclusion was, if you want people to drive more safely, what you should do is to take way all of these safety devices and install sharp spikes on the dashboards pointing at the driver. We adapt to all of these kinds of conditions.

Now, obviously this kind of a conclusion was incredibly controversial and a lot of people argue against this so-called “Peltzman Effect”. They argue that you know what you didn’t take into account the kind of driving. Is it city driving or rural driving? You didn’t take into account the skill of the driver, the education of the driver, the nature of the venue, is it during morning rush hour or evening commutes or during in the middle of the day? There are all sorts of factors that they claimed he did not take into account. And so, this paper literally launched hundreds of additional studies to verify or refute the Peltzman effect. In some cases, they confirmed it and in other cases they contradicted it and it wasn’t until 2007 that finally two economists came up with one particular venue where all of these other effects were controlled for. Right. Do you know what that venue was? Can you guess where you can basically control for all of these other effects and so therefore what you are focusing on is getting to your destination a little bit sooner? What would that venue be? What is it? Yeah, exactly the race car driving. So, in 2007 these two economists Sobel and Nesbit, they analyzed that the number of accidents in NASCAR racing when they introduced safety measures and it turns out that this is a real problem for NASCAR because in that setting, every time they introduced a safety device, titanium reinforced struts or additional protection for roll cages, every time they introduced these safety enhancements, the number of accidents and deaths went up. Didn’t stay the same. It increased.

If the only thing that matters is getting to your destination a little bit sooner than your competitors, if I tell you that your race car is slightly safer, you will push that to the limit and beyond. It is human nature.

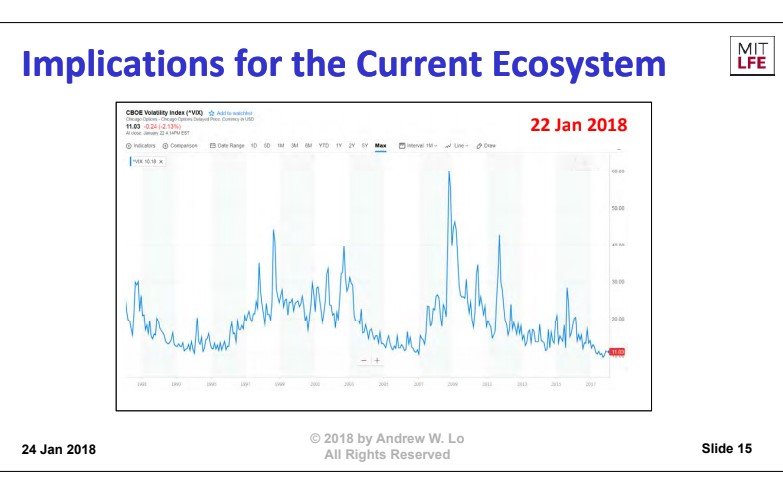

Now, this has some pretty significant implications for finance, particularly today when we happen to be sitting at a time where we are near historic lows in stock market volatility.

Given how low the volatility in equity markets, investors are adapting to that and what do you think they are going to do? What do you think happens when all of a sudden, I give you something that now has a higher Sharpe ratio that has lower perceived risk? You are going to want to do more of that right? That is what has been happening right now as we sit here and enjoy this wonderful bull market and wonderfully low level of volatility.

Of course, what goes up eventually does come down and so as we start adapting to this kind of a new low level of volatility there is a rude awakening that we are facing. So, something to keep in mind. So, that is one important implication of adaptive markets. Markets are not the same over time and the population of investors they are not the same over time. They have changed and they adapt and sometimes that adaptation is positive and beneficial, but other times that kind of adaptation can be quite dangerous and detrimental.

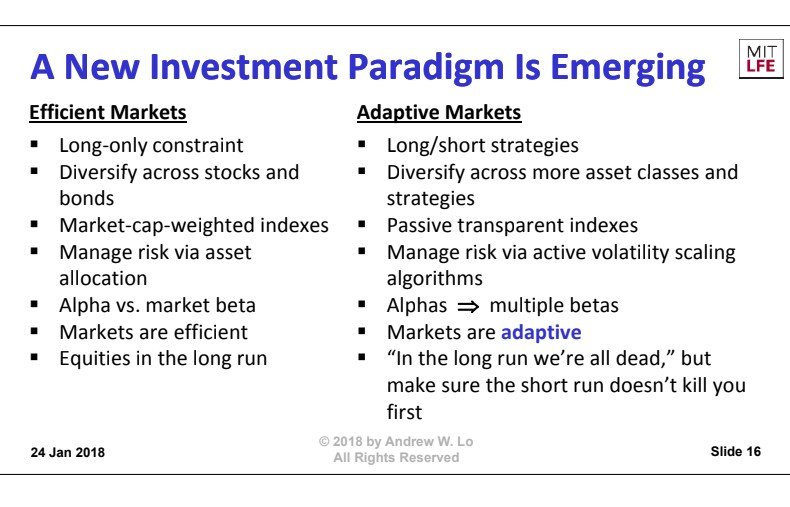

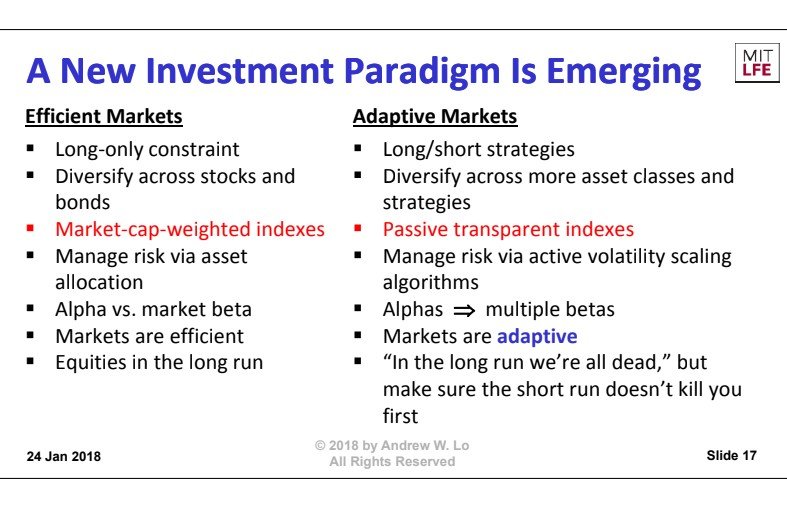

So, I am going to give you another example about this new world order of investments and describe to you a whole bunch of different implications of efficient markets and how that compares to adaptive markets. I won’t have enough time to go through all of these, but I want to give you at least one example to show you that all of the things that we take for granted as being naturally and implication of the current framework that we live in things like long only investments are just fine, you don’t have to worry about shorting or that you can control your risk by asset allocation or that you can invest for the stocks in the long run, every single one of these tenets of modern finance has a different interpretation and a different implication under the lens of adaptive markets.

So, I want to focus just on one of them which is the notion of passive investing and indexation.

Passive Investing

That is a hot topic, because obviously the amount of money that has been flowing into indexed products, ETF’s, futures and other related instruments has been dramatic over the course of the last several years. In fact, Vanguard just passed its four trillion-dollar mark. It is a kind of a milestone for how investors are thinking about investing.

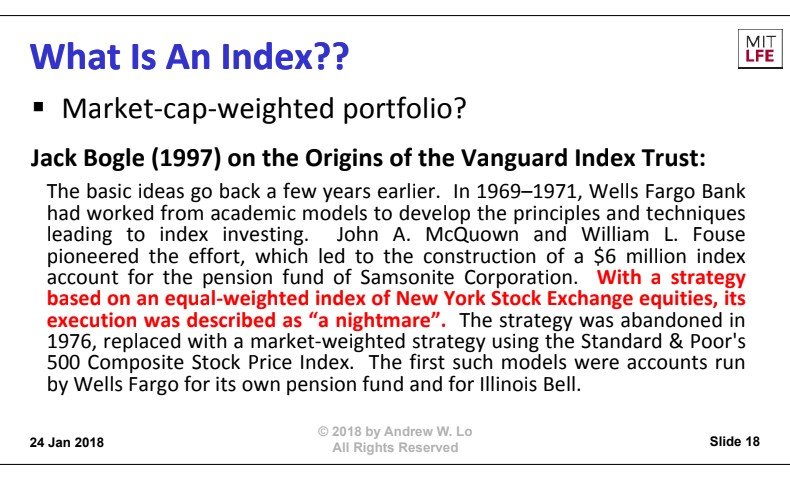

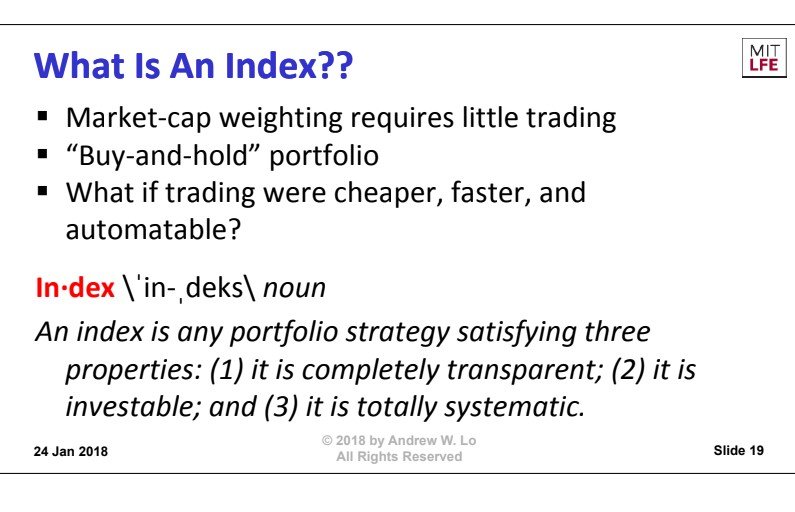

So, I want to start by talking about what exactly an index is.

What is an index? What is the definition of an Index? Can anybody give me a quick one liner of what an index is to you? What does it mean from a practical perspective? Yeah, exactly and typically one of those weights, do you know market caps? Right, exactly a market cap weighted portfolio. That’s the natural knee-jerk reaction of what an index is and the idea behind the index is that we are not using any investment acumen or alpha. It is meant to be passive. You are going to just buy it and hold it

and leave it there. That is really what an index has come to mean in the industry. Now, who gave us that definition? Who if you had to identify one person that was responsible for the passive investment management industry? Who would you place that honour on? Jack Bogle. Absolutely, the founder of Vanguard.

I think there is a universal agreement that Jack Bogle is the man.

When you ask Jack Bogle though, he actually gives credit to somebody else. Now Bogle was the first to create the first passive mutual fund, but he was not the first to engage in passive investing. In a graduation speech in 1997, Mr. Bogle gave credit to these two individuals, Jack McCown and Bill Fauss of Wells Fargo bank. The basic ideas go back a few years earlier. In 1969 to 1971, Wells Fargo Bank had worked from academic models to develop the principles and techniques leading to index investing. McCown and Fauss pioneered the effort which led to the construction of a six-million-dollar index account for the pension fund of Samsonite corporation. With the strategy based on an equal weighted index of New York Stock Exchange Equities, its execution was described as a nightmare and ultimately it was abandoned in favour of market cap weights.

Now when I read this, I was blown away. Because I didn’t understand what the big deal was, what was so hard about a portfolio of a hundred equally weighted NYSC stocks? And you know what the problem was? In 1969 if you constructed a portfolio of 100 equally weighted stocks, at the end of the month, that portfolio is no longer equally weighted. Right? Because the prices the stocks of the prices that went up, they are over weighted and the stocks of the prices that went down are under weighted and so you have to rebalance that portfolio every month and it turns out that rebalancing a portfolio of a hundred stocks every month in 1969 was an operational nightmare. Remember that in 1969 a spreadsheet was a piece of paper with lines on it and somebody had to do the back-office accounting reconciliation and all the trading kind of calculations. It took a month to trade a hundred stocks and do the clearing. Literally a month. And so ultimately it was just too hard. It was technologically too difficult. They gave it up and they decided to go to market cap weighting.

Market cap weighting has this wonderful property, that once you construct it, you never have to touch it. Because once a market cap weighted portfolio always a market cap weighted portfolio. The only thing you have to do is deal with index inclusions and deletions. But that is it. Its buy and hold. You never have to touch it. So, this was really striking to me because what this tells me is that there is no magic behind market cap weighting. We have decided that market cap weighting is a good thing to do because of technological constraints. That is why we do it. What if it told you that technology has advanced? What if I told you that it is possible to trade quicker, cheaper and to do all the back-office reconciliation calculations at a touch of a button? What if all of this could be automated?

Well, if that were the case, maybe we would not choose market cap weighting any longer. We would maybe we would pick something else. So, what I would like to do is propose to you a different definition of what an index is and here is my definition. An Index is any portfolio that has three characteristics and here are the three

- It is totally transparent. Meaning everybody knows how it was constructed.

- It is investable. Meaning that you could put a hundred million dollars to work in that portfolio and actually get the return that the index will show over the course of a month.

- Most importantly, it is totally systematic. Rules based and everybody knows the rules.

Those three are what the key characteristics are for what we think of as an index, because for passive investing what you want to be able to say is I don’t want to give my money to you, the manager, because look what I can get with this portfolio that requires nothing more than my sticking it into this very very simple vehicle. In order for you to be able to say, “No I am not going to give the money to you, I am going to put it here”, you need these three things to happen.

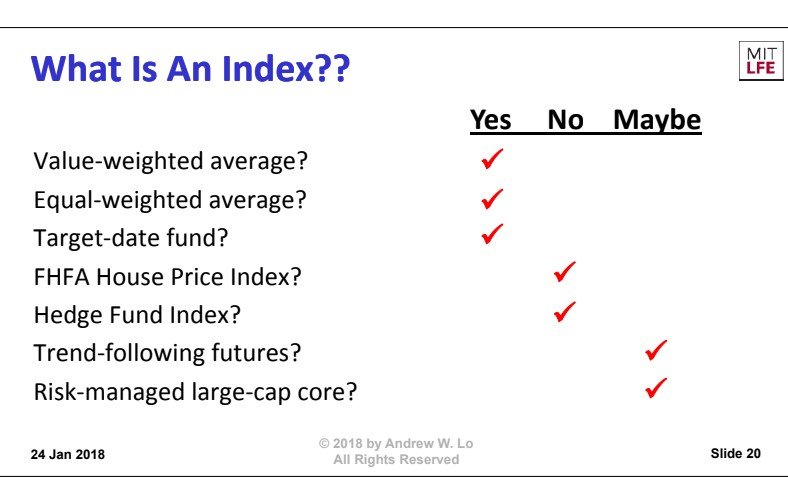

So, I am going to give you a surprise quiz now. I am going to ask you to apply this definition and tell me whether or not the following are actually indexes

based upon my definition, but not the industry’s definition.

So here is the first question.

A value weighted average, in other words a market cap weighted portfolio is that an index under my definition? Yes or NO?

Correct. Yes!

What about an equal weighted average. Like the very first index portfolio for Samsonite. Is that also an index according to my definition.?

Absolutely. Yes!

Ok. What about a target dated fund? You know the fund where we change the asset allocation as a function of how old you are how old you are close to retirement. Is a target dated fund and a index fund according to my definition?

Well it depends. Do you know the glide path? If you know the glide path, if you know the asset allocation rule, it is. Because it is totally transparent. Its systematic and it is investable.

Alright. What about the FHFA house price index. Is that an index?

It is not only not transparent and it is certainly not investable. Right. No, that is not an index.

What about the hedge fund indices? Are they indexes?

They are not investable and they are not transparent. Right?

Last but not least, a couple more trend-following futures, is that an index?

Well the answer is maybe it depends, is it rules based? Is it totally transparent? In that case it is, but many of the trend-following futures mutual funds have certain proprietary components. So, no, those are not. So, it depends.

How about large cap risk managed core product? Again, it depends. Maybe whether it is systematic or whether its transparent. You get the idea though. Right?

Spectrum Investing

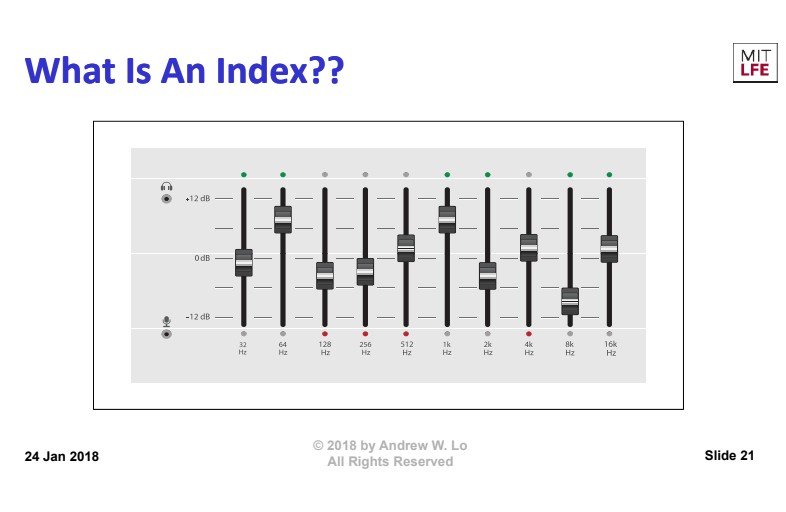

Why am I taking through all this, it is because it turns out that this new definition of an index opens up a whole ocean of possibilities for the investment community and for the investor. In order to give you an appreciation of that, I am going to take an analogy from music, particularly from audio files out there.

I don’t know how many of you are really serious about listening to music, but if you are, you will probably recognize this. Does anybody know what this is? Yeah it is a graphic equalizer. This is a device that my audiophile friends tell me is a Must-Have. What it does is that it allows you to control the amount of sound coming out of your speakers at different frequencies so that you can tailor the listening experience to your own particular needs. Now I don’t really know what my needs are for these different frequencies, but he tells me that it is actually very important. Sometimes you want more bass, sometimes you want more treble, this will allow you to do that. Imagine if we had this device for our investment portfolio. We had an equalizer that allowed us to dial up or down different characteristics. So, let me give you an example.

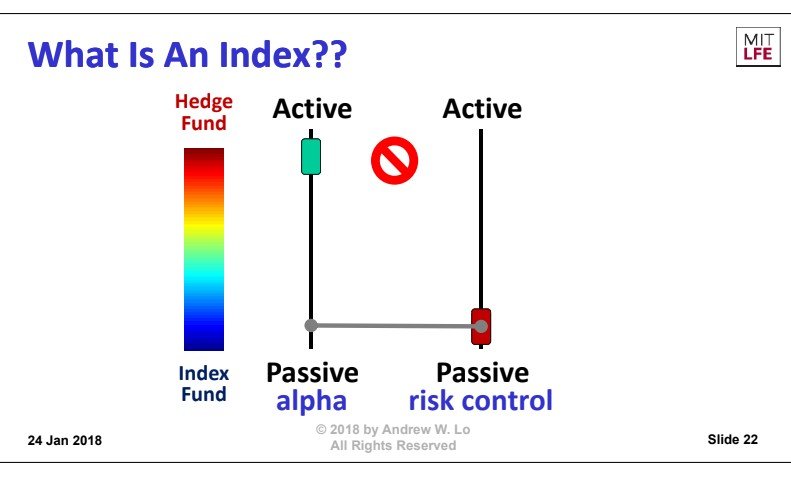

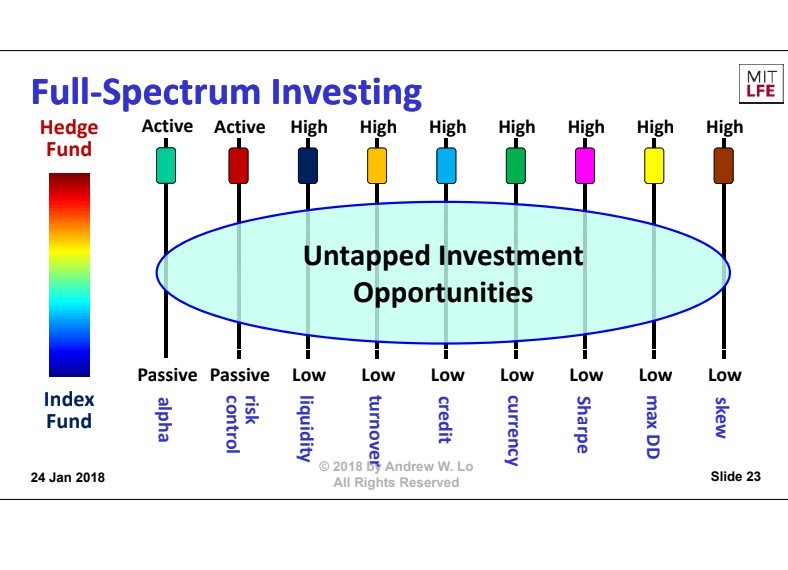

There is a very big spectrum of difference between a hedge fund and an index fund. Passive versus Active. Right?

And one way to think about that is alpha, this notion of unique investment acumen. Hedge funds have it. At least they claim they do. Those skeptics don’t believe it they would prefer to put money in passive index funds, where there is no alpha, it is all about Beta and so sometime during the 1960’s and 70s, we as a society decided to be skeptical about alpha and we decided to dial down the Alpha and go focusing on beta. Right?

At the same time that we did that we also decided to relinquish our roles as risk managers. The typical index fund has no risk management. I mean it is you get the S&P500, that is your portfolio. If the S&P500 goes down by 50%, that is what you are going to get. You own that 50% loss and by the way the S&P did go down by 50% between 2008 and early 2009. So that is not just a hypothetical example.

No risk management. It is an index passive investing. If it goes down, you go down with it and sure enough that is exactly what you see on this graphic equalizer chart. Those two things are linked. If you want risk management, the place to get it is back in the hedge fund community. Because hedge funds manage their risk in an excruciating detail. It turns out that this is a false dichotomy. We do not have to stand for this. There is no reason why we cannot break this link. We can actually now, thanks to technology, we can now change that and dial down the Alpha while maintaining our risk management. So, this is an example of adaptive markets at work. Technology has given us number one, the ability to go away from market cap weighting, but number two to change our mix of Alpha versus beta and Sigma variance risk and in fact if you take this to its logical conclusions, what you get is what I call full spectrum investing. There are many different characteristics of a portfolio. Liquidity, credit exposure, foreign currency exposure, so on and so forth and right now, we have got very little in between those two extremes across these characteristics.

There is a whole ocean of untapped investment opportunities and so with the proper tools and with the proper technology, we can dial up or down those kinds of different exposures in order to tailor the investment experience for each and every one of you here today.

Precision Investing

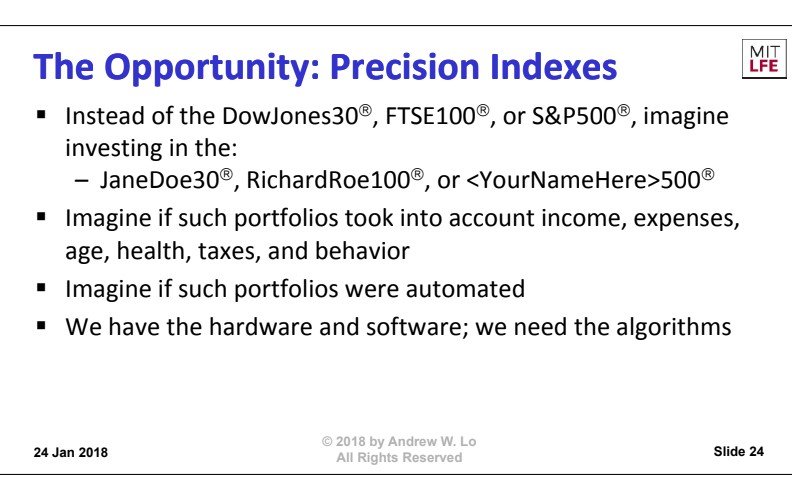

So, what am I talking about well, here is the vision –

Precision Indexes. You have all heard about precision medicine. The idea that I can tune the particular therapy to your specific genetic makeup, well there is no reason why we can’t do that from the financial perspective.

Instead of the S&P500 or the Russell 1000, imagine having your individual index tailored to your particular circumstances. Imagine that index constructed to take into account your income, your expenses, your life goals, all your constraints. This is what I call really smart Beta and imagine if we can automate this so that the product is just running all the time. Now, you might think this is like Robo advisors. It is not Robo advisors. We are not there yet. It turns out that we are close, but we have not achieved this.

We have the hardware, we have the software, we have the telecommunications. But there is a missing piece and that missing piece is that we don’t have the algorithms. We do not understand how to create these kinds of strategies. Now, I have to tell you that this idea is not new, so I am going to read to you something from an article that was published a few years ago titled “Personal indexes” in the concluding paragraph of this article, this author wrote the following:

“Artificial intelligence and active management are not at odds with indexation, but instead imply a more sophisticated set of indexes and portfolio management policies for the typical investors something each of us can look forward to perhaps within the next decade”.

Who was this incredibly prescient and brilliant author who wrote these words? Your truly. I wrote this in 2001, so you could argue I was a bit off and late, but actually no I think that you know as of 2011 we had a number of products that were automated in a number of ways, but we are not there yet and the reason we are not there yet is because of this.

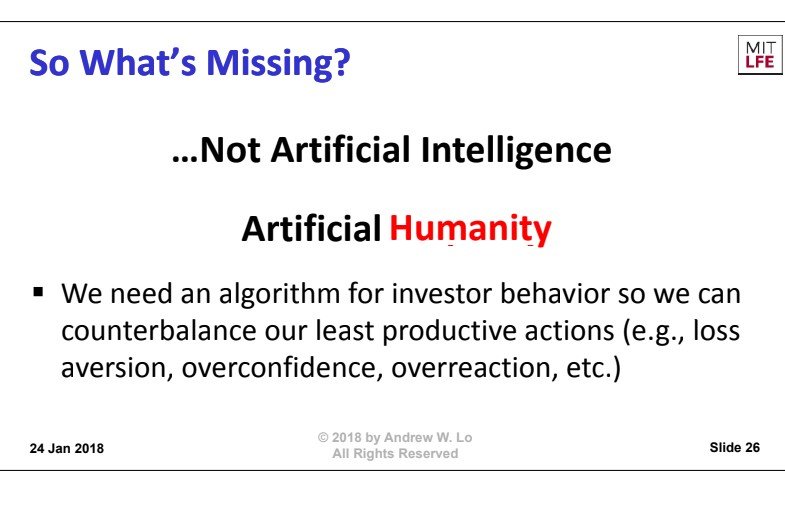

It is not because of artificial intelligence. We have plenty of artificial intelligence.

What is missing is artificial stupidity.

We don’t yet know how to model human behaviour in an algorithmic way. And until and unless we can do that, until we can actually model, not how people ought to behave, but how people actually behave, we are not going to be able to develop the products and services that address those human foibles and inconsistencies and irrationalities.

Artificial Intelligence – Old School vs. Today

So, I am going to give you an example of this by talking about artificial intelligence. This is why I have to go from human behaviour to computer science. I want to describe to you what has happened over the course of the last few years in AI because something remarkable has occurred that ultimately will have an impact on financial markets. And to make that point, I am going to give you an example that distinguishes between human versus artificial intelligence. So, the example of AI that I want to bring to bring up here is something that all of us have dealt with before and that has to do with online shopping.

A few years ago, I started getting interested in biomedicine and healthcare industry and so I decided to order a book on one of the most successful biotech companies in the industry, Biogen Inc Common (NASDAQ:BIIB) and Genentech. And so, Genentech’s book was relatively easy to purchase. I went on to Amazon and I clicked on you know add to the Shopping cart and the moment I did that, Amazon does this thing which I just absolutely detest, you know what it is. What they did was they showed to me five books that people who bought that book also bought and I had to have two more of those. It is really, really nasty, nasty piece of technology. Very effective.

This is an example not of old AI, but of new AI. This is very different than how we used to think about AI in the 1970’s and 80’s and I know that because I was there then and I actually worked a bit in that field and I can tell you right now that things are so different and let me tell you how they are different.

In the old days in the 1980’s, AI was tantamount to constructing what are called expert systems. How many have heard of the term expert systems?

It has a very interesting division in the show of hands. Everybody under the age of 40 will not have heard of that term. If you are over 40, my guess is you will.

An expert system was a rather lengthy piece of software, that tried to replicate a particular aspect of human behaviour and it did so by trying to account for every possible contingency and then coming up with the optimal response to that contingency. Very much like what an economist would think we ought to behave like as a human and so a good example is a piece of software that created a robotic arm to play ping pong.

I was quite excited about this because I loved ping pong when I was young but I could never find anybody to play with me, so I would I wanted to get a robotic arm. Didn’t exist. But there was some faculty that were doing research on it and I think it was Carnegie Mellon that developed the first robotic arm that did this. They created a robotic arm to play ping pong, not very well, but well enough to be able to hit the ball across and play you know reasonably consistently over a period of minutes. That piece of software it must have been a two hundred thousand lines of code, which is back in the 1980’s, was a very, very big piece of code and what it did was to first of all identify the trajectory of the ball using Newton’s laws of gravity, move the ping-pong paddle in just the right way, calculate the appropriate angle of deflection and the coefficient of friction on the paddle surface and use the appropriate Newton’s force to be able to move that ball across the net. It was an incredibly complicated piece of code and it worked, sort of. It could not beat a serious player, but it at least gets the ball over the net. That was AI back in 1980’s.

What’s AI today? Well today, you know what they do? They take cameras and they film Olympic level ping-pong players and they film them for a few hours and they take that footage and they store it and they decompose it into all the possible different positions and angles and various kinds of moves and they get the robotic arm simply to replay that data. In other words, they use large amounts of data and they simply draw from that database and appropriate example to control the robotic arm. The amount of code, very, very small – A few tens of thousands of lines. The amount of data – hundreds of gigabytes of video data. Big data and machine learning have completely transformed the space and back in the 1980’s we could not do this because we did not have the ability to store data. I don’t know how many you remember but, I bought one of the first IBM PC and I paid $3,000 for the PC and it was an extra $1000 if you want 125K of memory.

What we are doing today with storage being so cheap and using machine learning methods on large amounts of data, this is actually much closer to how human intelligence works. We are building machines that are closer and closer to how we think and that is both exciting and frightening. So, let me give you a couple of examples of that and I will wrap up. So, I am going to give you an example of how we all engage in this kind of very similar pattern recognition the way that Amazon and other online retailers do and I will start with something that all of us are implicitly good at, which is identifying

friend versus foe. This is something that from an evolutionary perspective was hardwired into us at the very early stages. Otherwise we would not be here today to talk about it.

Artificial Intelligence – Human Behavior

So, I am going to show you an image and ask you to identify as quickly as possible whether or not this image is a friend or a foe. Is it threatening or not threatening. Alright? Here we go.

Friend or Foe? Who knows. You can’t tell right. All you see is a bunch of blotches but friends that tell me that you all of you are very friendly here because your natural reaction is friends in other audiences the immediate reaction is foe. I don’t know what it is, I am scared of it. It can take it out. But you can’t really tell. Not enough data in this rather pixelated image.

How about this? Friend or Foe?

Foe, wow, interesting. That was a big change. Okay. Well let me show you one more image with even more data and here it is. So, this is your truly being stalked by a ninja. So, definitely looks like a foe, but actually upon further reflection and examination, the ninja is not real. This was taken at the Washington DC spy museum. I took a selfie with this ninja statue and you can tell that it is not at all threatening. Data, Big Data makes a big difference. So, having a high-resolution image is pretty important for determining friend or foe.

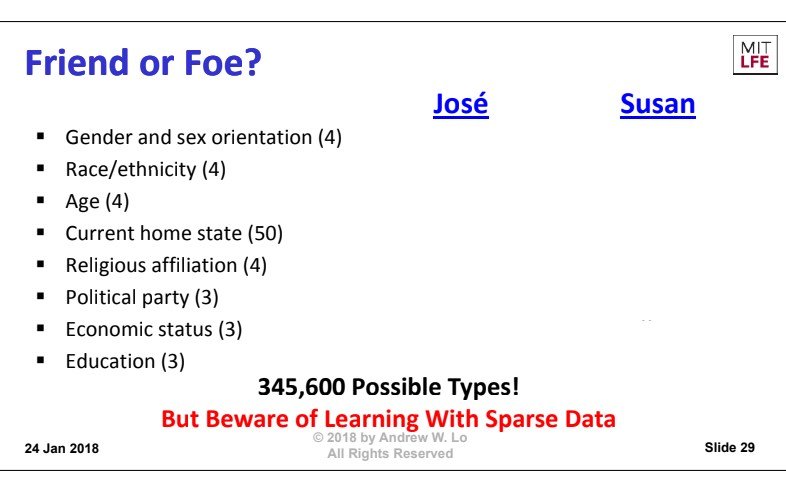

It turns out that we do this in a more refined way when we are meeting people to see whether or not they are friendly or not and so I want to give you one more fine example of this and the refined example has to do with cocktail parties that you might happen upon over the course of an evening as you go from person and person and group to group you will learn things about different people and that allows you to determine friend or foe in a much more sophisticated manner. So, let me just give you a specific example. At the cocktail party you will run into people and engage in casual conversation and during the course of an evening conversation you will talk about things you will learn stuff about the other party. Things like what their gender is their sexual orientation, race, ethnicity, age group, current home state, religious afflictions so on and so forth and in parentheses are the broad number of categories of each. So, two genders, two sexual orientations roughly four combinations and so on.

So, I am going to do little experiment here. I am going to tell you about two specific individuals that I have met and after I tell you about them I am going to ask you to make some judgements about them. okay? And the two people I am going to tell you about are Jose and Susan. So, Jose happens to be a young professional gay Latino male who lives in state of California. No religious affiliation. He is a democrat middle class and has an MBA. Now that’s Jose.

Now I am going to tell you about Susan. Susan is a middle-aged white heterosexual female from the state of Texas, Christian, Republican, affluent and has a Bachelor of Arts. That is Susan.

Okay I am going to ask you three questions now about these two individuals.

First question – You are doing an internet start-up in Silicon Valley and you need to hire somebody to help out with that effort. Who would you rather hire? Jose? Or Susan? How many people would hire Jose as their internet start-up colleague? How many of you will hire Susan? Okay.

Second Question – you are organizing a fundraiser for breast cancer campaign. You want to raise money to help deal with breast cancer. Who would you hire to help you organize that fundraiser? How many people hire Jose for that fundraiser? How many people hire Susan for that fundraiser? Okay.

Third question – You are working at the internal revenue service as an auditor and you need to audit one of these two individuals. You can’t do both, but you need to figure out which one of them is more likely to be cheating on his or her taxes. How many of you would audit Jose? How many of you would audit Susan?

Wow. That is remarkable. I can’t believe how judgmental you people are. I mean you know you don’t know these people, but yet you are making decisions about who to hire, who to throw in jail for tax evasion. Now it is true I asked you, but you didn’t really hesitate, did you? What you are doing is exactly what Amazon does. You are actually using machine learning big data, except its Human learning in this case. You are searching your database of all the people that you know who have done fundraisers and seeing which one is most like Susan versus Jose and how the outcome went and picking on the basis of that. It is Human nature and it is not perfect by any means, but it is better than nothing and the reason I know it’s better than nothing is that we are here today to talk about it. We survived. This is a survival mechanism and it is a very sophisticated one.

How sophisticated? Well, if I go through all the different combinations of the types of people that you will now be able to categorize them into the number of buckets, you now have in your brain, because of these characteristics. If you do the math, there are 345,600 unique combinations of personality types in your database. This is more pixels than in a 600/800 photograph. So, just by talking to the people and finding out a few facts about them, you can put them into various different buckets and then search your database to see which of those buckets have been more successful for fundraising and which have been more successful for doing start-ups.

The problem with this algorithm that all of us use is that it is based on very, very sparse data. What I mean by sparse data is how many people here have met more than 345,600 people in their lives? I actually had one marketing person raise his hand when I guess. What it means is that for most of us virtually all of these cells all of these buckets are empty. We have no data and this is one of the real problems with fake news. Fake news fills in these missing cells and if you get them filled in with the wrong information, it will affect and change your behaviour in dramatic ways. We all exhibit biases based upon missing cells. We are all going to face gender bias, racial bias, religious bias. I am not excusing it, but I think we can explain it and if you understand it, you can do something about it.

What we need to do is to change the database. If you want to eliminate bias, we need to go into those cells and change the entries into something that is correct as opposed to misleading.

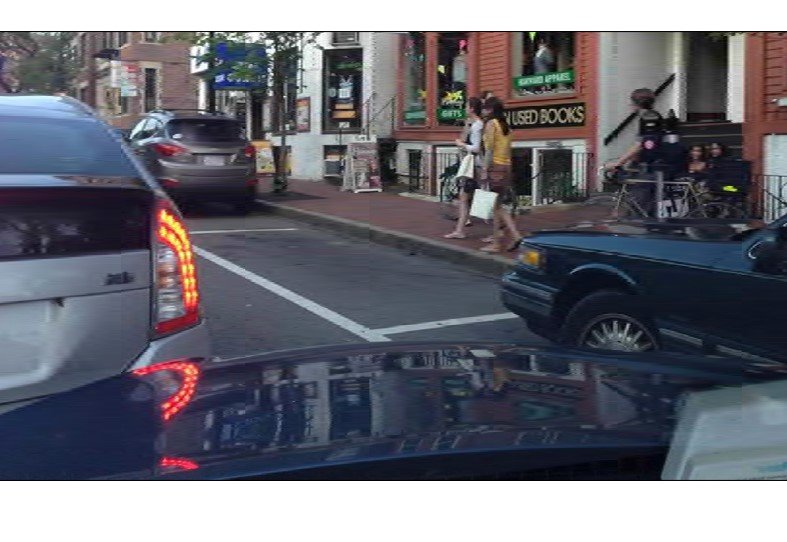

So, it is more than this though, it is not just cells, it is not just data. It is interpretation of the data. So, the last two examples that I am going to give you and then wrap up, is that we respond not to data, but to narrative, to interpretations of the data. So, just like I explained, you are not just looking at statistical relationships. You are trying to predict whether or not Susan or Jose is going to be good in one Character or the other. In that kind of prediction, you need this narrative and it turns out that narrative, the stories we tell ourselves about how people behave that can actually affect our reality. So, I want to illustrate that to you with an example and the example has to do with this. Does anybody recognize this image? Yeah what is that? Very good. Exactly. Thank you.

It is Harvard Square. How many people here visited Harvard Square? How many people have ever driven into Harvard square and how many people of those who have driven have not been able to find parking

in Harvard Square? So, until recently my rule of thumb living in Cambridge and in Boston is never ever drive into Harvard Square. You could take the take the bus, take an Uber. Do not drive your own car into Harvard Square. You will never find parking. And I use this rule of thumb until recently when I was taught an algorithm for dramatically increasing my chances of getting parking in Harvard Square and I am going to share that algorithm with you today because most of you don’t live in Boston and will not compete with me. But you know this algorithm actually works here in New York. So, if you want to get parking in Times Square, this will work too.

Let me tell what the algorithm is. Before you enter the place where you want to get parking, before you do that either at a stop light or pull aside and be safe so you can do this. Close your eyes and utter the following incantation. The incantation is rabbi Mahoney rabbi Mahoney rabbi Mahoney. You say that three times and you will magically be able to get parking with much more likelihood than before. Now I know a few of you are giggling. You know you don’t believe me and you know I didn’t believe this either when I first heard it. And then I tried it and it really works. Now you may be too embarrassed to even try it. So, if you are, here is a tip. Tell one of your friends and have them try it and they will come back and tell you and thank you for this incredible insight. You know and here sure enough is my parking space that I got by using this. But what is more interesting is not that it works, but why it works and it took me a while to figure this out. I actually literally went through the process of trying this a few times measuring you know how long it took me to get a space and you know how it went about it and after doing all of that, I finally realized what was going on and it actually has to do with this narrative.

It turns out that when I went through this process and uttered the incantation the very act of doing so implicitly caused a small portion of my brain to acknowledge that no it was not impossible to get a parking space in Harvard Square that there was a glimmer of hope no matter how small it now existed in my brain, because otherwise I would not bother doing the incantation and go through this really stupid exercise, but I did so. And because of that change in my narrative, because I changed my narrative from “Oh it is impossible to get parking” to “You know it’s very, very unlikely, but you know that there is a slight chance that I might be able to do it”.

Because of that narrative change, I noticed something. When I drove into Harvard square, I drove more slowly. I looked more carefully down the side of the road to see whether or not any brake lights would turn on and indicate a car is about to pull out. I would now allow pedestrians to cross in front of me, instead of trying to run them over, because they might be going to a car and giving me a space. I changed my behaviour because of that narrative and that change in behaviour actually increased the chances that I would get a space.

Sometimes, things need to be believed in to be seen and that is a remarkable lesson that I learn from this exercise. So, what we think of as reality is not nearly as real as we think. Reality is often what we make it and the narratives that we use in all of our daily lives. Narrative is the key.

Evolution of Thought

And so, I want to conclude by talking about the subtitle of my book “Evolution at the speed of thought”. What I am getting at there is that narrative changes as a function of circumstances and it is critical for us to manage that narrative, so that we end up doing the things that we want to achieve as opposed to allowing those narratives, those pieces of fake news that control us. So, I want to leave you with one final story about the power of narrative and open it up for questions and discussion and that has to do with a hiker by the name of Aron Lee Ralston who on April the 26th of 2003 was hiking in a remote part of Utah called Blue John Canyon. This part of Utah that where there is no cell phone coverage, there are no highways, there is nobody around for hundreds of miles. You are literally out completely in the desert and he was an experienced hiker. But during the course of his hiking, he slipped down a crevasse, fell and a 600-pound boulder fell on top of him and pinned his right arm to the face of the crevasse wall. You probably know who I am talking about, because he wrote a book that was called between a rock and a hard place. In a movie that was made about him with James Franco called “127 hours”. He was pinned for 127 hours in that crevasse, before he decided to do what most of us consider unthinkable. He took out a dull multi-tool and amputated his right arm below the elbow. How did he do that. I don’t mean literally how. I am not going to show you any video of that, but I mean how does somebody do that how does somebody decide after five days that okay now it’s time for me to cut my right arm off and it was a gruesome, gruesome process that I won’t describe to you, but it took some incredible amount of fortitude to do that. Well, if you read the book, he describes how he did it. It has to do with narrative and this is the narrative that he used.

“A blonde 3-year-old boy in a red polo shirt comes running across a sunlit hardwood floor and what I somehow know is my future home. By the same intuitive perception, I know the boy is my own. I began to scoop him into my left arm using my handless right arm to balance him and we laugh together as I swing him up to my shoulder. Then with a shock the vision blinks out I am back in the canyon, echoes of his joyful sounds resonating in my mind creating a subconscious reassurance that somehow, I will survive this entrapment, despite having already come to accept that I will die where I stand before help arrives. Now I believe I will live. That boy, that belief changes everything for me. Now what is amazing about this story is that in 2003, Aron Lee Ralston was not married, did not have a girlfriend, did not have a kid. This is a total figment of his overactive imagination. He didn’t get married till six years later and a year after that he had a son and ultimately realized his vision. But it was that narrative that got him to do this.

Financed desperately need new narratives. Since the financial crisis, finance has received a very bad rap and part of it is deserved. But at the same time finance is the core of fuelling innovation and we don’t want to cut our noses off to spite our faces and I am afraid that we are in the midst of that process because finance has been so heavily criticized.

Regulators, practitioners were all in the midst of self-discovery and recrimination and I want to argue that finance is not the problem, it ultimately could very well be the solution of many of the society’s problems. And so, with the help of the Museum of American Finance and the Gabelli School of Business, with all of you, I think we can all get to better narrative.

Thank you.